Category Archive: Theology – Liturgical

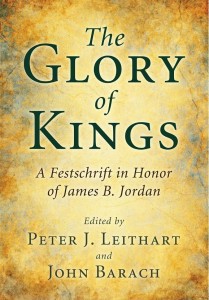

The Glory of Kings

It’s finally available: Peter J. Leithart & John Barach, eds., The Glory of Kings: A Festschrift in Honor of James B. Jordan (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2011).

Foreword — R. R. Reno

Introduction — Peter J. Leithart

PART ONE: BIBLICAL STUDIES

1. The Glory of the Son of Man: An Exposition of Psalm 8 — John Barach

2. Judah’s Life from the Dead: The Gospel of Romans 11 — Tim Gallant

3. The Knotted Thread of Time: The Missing Daughter in Leviticus 18 — Peter J. Leithart

4. Holy War Fulfilled and Transformed: A Look at Some Important New Testament Texts — Rich Lusk

5. The Royal Priesthood in Exodus 19:6 — Ralph Allan Smith

6. Father Storm: A Theology of Sons in the Book of Job — Toby J. Sumpter

PART TWO: LITURGICAL THEOLOGY

7. On Earth as It Is in Heaven: The Pastoral Typology of James B. Jordan — Bill DeJong

8. Why Don’t We Sing the Songs Jesus Sang? The Birth, Death, and Resurrection of English Psalm Singing — Duane Garner

9. Psalm 46 — William Jordan

PART 3: THEOLOGY

10. A Pedagogical Paradigm for Understanding Reformed Eschatology with Special Emphasis on Basic Characteristics of Christ’s Person — C. Kee Hwang

11. Light and Shadow: Confessing the Doctrine of Election in the Sixteenth Century — Jeffrey J. Meyers

PART FOUR: CULTURE

12. James Jordan, Rosenstock-Huessy, and Beyond — Richard Bledsoe

13. Theology of Beauty in Evdokimov — Bogumil Jarmulak

14. Empire, Sports, and War — Douglas Wilson

Afterword — John M. Frame

The Writings of James B. Jordan, 1975–2011 — John Barach

The book is currently available for order directly from Wipf & Stock for $40.00 (but there are discounts if you order more than 100). In a couple of weeks, it should appear on their webpage, and in six to eight weeks should appear on Amazon.

The King of Victories

In an essay in Angels in the Architecture: A Protestant Vision for Middle Earth, which I’m rereading, Doug Wilson comments on one of the names used for God in Beowulf. God is the “Lord of Victories”:

“No man could enter the tower, open hidden doors, unless the Lord of Victories, He who watches over men, Almighty God Himself, was moved to let him enter, and him alone” (ll. 3053-3057). Whether the victory is Grendel falling before Beowulf, or Satan crushed beneath the heel of Christ, God is the only One to bestow any victory.

The psalmist asked the God of Israel to rise up and scatter His enemies; whenever the Power of His right hand is pleased to do so, those enemies are driven before Him like smoke in a gale. The Church today is a stranger of victories because we refuse to sing anthems to the king of all victories. We do not want a God of battles, we want sympathy for our surrenders. We need to be taught to sing as Alfred the Great taught his men before going into battle — “Jesu, defend us” (43).

And that starts with us learning to sing the Psalms. Do we not have enemies? Do we not love our brothers and sisters who are being persecuted in the Middle East and in Darfur and throughout the world? How can we truly love them if we are not singing the imprecatory psalms and hymns like them, calling on the King of Victories to rise up and overthrow their enemies and rescue them?

Divine Love Made Food

This afternoon, I began rereading Alexander Schmemann’s wonderful For the Life of the World. Since I had just blogged about food as communion, I thought it would be good to pass on these quotations from the first chapter:

“Man is what he eats.” With this statement the German materialistic philosopher Feuerbach thought he had put an end to all “idealistic” speculations about human nature. In fact, however, he was expressing, without knowing it, the most religious idea of man. For long before Feuerbach the same definition of man was given by the Bible. In the biblical story of creation man is presented, first of all, as a hungry being, and the whole world as his food.

Second only to the direction to propagate and have dominion over the earth, according to the author of the first chapter of Genesis, is God’s instruction to man to eat of the earth: “Behold I have given you every herb bearing seed … and every tree, which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat….” Man must eat in order to live; he must take the world into his body and transform it into himself, into flesh and blood. He is indeed that which he eats, and the whole world is presented as one all-embracing banquet table for man. And this image of the banquet remains, throughout the whole Bible, the central image of life. It is the image of life at its creation and also the image of life at its end and fulfillment: “… that you eat and drink at my table in my Kingdom” (11).

Later on, Schmemann goes further:

“Man is what he eats.” But what does he eat and why? These questions seem naive and irrelevant not only to Feuerbach. They seemed even more irrelevant to his religious opponents. To them, as to him, eating was a material function, and the only important question was whether in addition to it man possessed a spiritual “superstructure.” Religion said yes. Feuerbach said no. But both answers were given within the same fundamental opposition of the spiritual to the material. “Spiritual” versus “material,” “sacred” versus “profane,” “supernatural” versus “natural” — such were for centuries the only accepted, the only understandable moulds and categories of religious thought and experience. And Feuerbach, for all his materialism, was in fact a natural heir to Christian “idealism” and “spiritualism.”

But the Bible … also begins with man as a hungry being, with the man who is that which he eats. The perspective, however, is wholly different, for nowhere in the Bible do we find the dichotomies which for us are the self-evident framework of all approaches to religion. In the Bible the food that man eats, the world of which he must partake in order to live, is given to him by God, and it is given as communion with God.

The world as man’s food is thus not something “material” and limited to material functions, thus different from, and opposed to, the specifically “spiritual” functions by which man is related to God. All that exists is God’s gift to man, and it all exists to make God known to man, to make man’s life communion with God. It is divine love made food, made life for man. God blesses everything He creates, and, in biblical language, this means that He makes all creation the sign and means of His presence and wisdom, love and revelation: “O taste and see that the Lord is good” (14, last paragraph break added).

Food as Communion

Recently, I’ve been reading Thomas Foster’s How to Read Literature Like a Professor, which has been occasionally illuminating, not only for reading literature in general but also in terms of reading the Bible. (I hasten to add that the Amazon reviews point out a number of genuine problems with this book, too.)

Reading literature (including the Bible) is not like doing math. When you do math and come up with a certain solution to a problem, you can go back and prove your solution so that anyone else who understands math can follow along with you. But “solutions” in literature aren’t often that way.

Sometimes, of course, you can point to a particular passage that spells out your point. Sometimes you can appeal to the grammar (“That verb is past tense and so it must be talking about something that happened in the past, not something that’s still happening today”) or to history (“The Scarlet Pimpernel is set during the French Revolution, which went through various phases, and therefore…”) to establish your point.

But sometimes you can’t. When a writer sets a scene in the winter and describes the bleakness of the setting, is that symbolism? Well, it sure feels like it sometimes, especially if what happened just before winter arrived is that the main character’s beloved left. When a writer includes a meal — think of the extended meal scene in the movie Babette’s Feast — is that a form of communion? You might think so, but it would be difficult to “prove,” because reading is not a science.

Foster’s book is intended to help readers spot things they otherwise might not. Food as communion is just one of the themes he spends time on, and his comments in that chapter are quite helpful, shedding light on Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (sometimes a meal in a story can substitute for sex), Anne Tyler’s Dinner at the Heartbreak Restaurant (why can’t the mother get the whole family to sit down together for a meal, until the end of the book?), and James Joyce’s “The Dead.” About the latter, Foster writes:

No writer ever took such care about food and drink, so marshaled his forces to create a military effect of armies drawn up as if for battle: ranks, files, “rival ends,” sentries, squads, sashes. Such a paragraph would not be created without having some purpose, some ulterior motive. Now, Joyce being Joyce, he has about five different purposes, one not being enough for genius. His main goal, though, is to draw us into that moment, to pull our chairs up to that table so that we are utterly convinced of the reality of the meal. At the same time, he wants to convey the sense of tension and conflict that has been running through the evening — there are a host of us-against-them and you-against-me moments earlier and even during the meal — and this tension will stand at odds with the sharing of this sumptuous and, given the holiday, unifying meal. He does this for a very simple, very profound reason: we need to be part of that communion. It would be easy for us to laugh at Freddy Malins, the resident drunkard, and his dotty mother, to shrug off the table talk about operas and singers we’ve never heard of, merely to snicker at the flirtations among the younger people, to discount the tension Gabriel feels over the speech of gratitude he’s obliged to make at meal’s end. But we can’t maintain our distance because the elaborate setting of this scene makes us feel as if we’re seated at that table. So we notice, a little before Gabriel does, since he’s lost in his own reality, that we’re all in this together, that in fact we share something.

The thing we share is our death. Everyone in that room, from old and frail Aunt Julia to the youngest music student, will die. Not tonight, but someday. Once you recognize that fact (and we’ve been given a head start by the title, whereas Gabriel doesn’t know his evening has a title), it’s smooth sledding. Next to our mortality, which comes to great and small equally, all the differences in our lives are mere surface details. When the snow comes at the end of the story, in a beautiful and moving passage, it covers, equally, “all the living and the dead.” Of course it does, we think, the snow is just like death. We’re already prepared, having shared in the communion meal Joyce has laid out for us, a communion not of death, but of what comes before. Of life (13-14).

I don’t know that Foster is right to say that all meals in literature are communion in one way or another. If a writer says, “I was grabbing a burger at Joe’s when the trouble broke out,” the burger isn’t likely to be communion. Food serves other roles beyond just communion. Food can be fuel; it can also be reward.

But it does seem likely to me that any extended meal in a story is going to be significant (why else write about it?) and that shared food — or even, as Foster mentions in the chapter, shared cigarettes — forges bonds between people, not just in stories but in real life. Of course, as in the example from Joyce, meals may also be taken in isolation or may be times of hostility, not communion, and the lack of communion in such cases may be significant.

The point, then, is not to take every meal as “communion” but to have communion on your mind when you come to the meal and to ask “Why is this here? What’s really going on? Are these people being bonded by the food they’re sharing? If not, what else might the author be showing us?”

God has designed food as a form of fellowship. Think of the dietary laws in the Old Covenant and how they symbolize the bonds that Israel may or may not form with the Gentiles. Think of the sacrificial system, where the worshiper is represented by his offering, which is then consumed in the fire on God’s altar as “food for God.” That’s what we want to be, and symbolically that’s what’s happening to the worshiper. Think, too, of the times people prepare a meal for the Angel of Yahweh, sometimes without recognizing Him, and He refuses to eat with them. You don’t usually eat with people you’re angry at, and neither does God. And think, of course, of the Lord’s Supper in which we partake of Jesus, the great sacrifice, and are nourished by Him, but in which also we become one bread, one body, with one another.

Without committing ourselves completely to Foster’s dictum (“food is communion”), his chapter ought to alert us to a common function of meals in the stories we read and especially in the Bible. If you’re interested in pursuing more food theology in the Bible, I’d highly recommend Peter Leithart’s Blessed Are the Hungry.

Psalm Singing

In his lecture entitled “Introduction to Worship,” available here, James Jordan points out that one way to tell what Satan hates is to see what things that God wants in worship are missing or abused. What does Satan hate? One thing he hates is Psalm singing. Says Jordan,

The other thing the devil does not want is congregations singing the Psalms because the Psalms are full of holy war stuff. If you start singing the psalms, you start getting iron in your bones.

You know that Psalm 68, “Let God arise and let His enemies be scattered,” was the marching song of the French Reformation. They would sing it as they went into battle. The Huguenots in France would sing it all the time. Of course, they didn’t have air conditioning then, so the windows were open and all the Catholics heard it, and it made all the Catholics so afraid that eventually the king outlawed singing Psalm 68 in public. So they’d go around whistling. And they had to outlaw whistling that melody.

Now, people are not afraid when they hear us sing “’Tis So Sweet to Trust in Jesus.” They are not worried about you.

This move away from Psalm singing, it seems to me, has taken more than one form:

(1) Many churches do not sing the Psalms at all. They may sing hymns or gospel songs or praise songs, but they don’t sing the Psalms. In some of these churches, the Psalms are read; they may even be read responsively. That’s better than nothing, but it’s also rather strange, isn’t it? The Psalms were written to be sung. David didn’t simply read them. The Levites at David’s tabernacle didn’t simply read them out loud. They sang them. If you went to a performance of Handel’s Messiah, you’d be pretty disappointed if the performers read the text instead of singing. But in many churches, the Psalms are not sung and, in most services, are not read. And what that means is that the Psalms do not shape the piety, worship, expectations, language, biblical understanding, and so forth of the Christians in these churches.

(2) In some churches, a few Psalms are sung. If you look in a hymnal (e.g., the Trinity Hymnal produced by the OPC and PCA), you won’t find all the Psalms. You’ll find only some of them.

(3) There are songs that incorporate only a line or two of a psalm. Take the well-known praise song “As the Deer.” If you look at the first two lines, you’ll see that they are drawn from Psalm 42:1. But immediately the song leaves Psalm 42 behind. There are alternate stanzas that incorporate more of the psalm, but I certainly didn’t learn them and I doubt that a lot of Christians have. This is not Psalm singing.

(4) Most of the Psalms that are sung in churches — and I’m talking about churches that are committed to Psalm singing — are metrical Psalms. That is, someone has taken the Psalm and paraphrased it, arranging the words to fit a rhyme and rhythm scheme. Doing so necessarily requires you to depart from a strict word-for-word translation of the Psalm. For instance, “God” doesn’t rhyme with “sword,” so perhaps you change “God” to “Lord” to make the rhyme work. The length of each line of a metrical psalm has to be a certain number of syllables with the accent falling in a certain place (“Da-DA da-DA da-DA da-DA”), so what do you do with a long line in the Psalm? You abbreviate it to make it fit. At times, you rearrange words, producing something like what Jordan calls “Psalms by Yoda” (e.g., “You’ve raised like ox my horn”).

Do these changes really matter? Yes. I’m not opposed to singing Psalm paraphrases, and I particularly love the Genevan psalms. They’re still, to my mind, the greatest versions of the Psalms produced. But nevertheless they depart from a strict translation of what God actually said, and I think it is important that we learn to sing God’s Words and not our paraphrases of them.

Metrical Psalm singing, good as it can be, is not full Psalm singing. A metrical Psalm is to a Psalm what a sermon is to a passage of Scripture. It’s a paraphrase, a poetic rendition, an explanation. But what about singing a good translation of the Psalm itself? Who would want to settle for a sermon instead of a Scripture reading? Who would settle for a poetic paraphrase instead of a Scripture reading?

But to sing a good translation, word for word, would require either a through-composed Psalm (and they’re somewhat hard to learn, given that there’s no repetition in them) or — horrors! — chanting. And immediately the objections start: “We can’t chant!” Why not? “Chanting is Roman Catholic!” No more than saying the creed or a host of other things we do in church. “Chanting would be too hard.” But aren’t a lot of worthwhile things hard at first? The question is: Do we really want to sing the Psalms or not?

(5) When churches do sing the Psalms, they sometimes do so in ways that rob them of their power.

* C. S. Lewis said that a lot of hymns in his day were “fifth-rate poetry set to sixth-rate music,” and that’s true of some metrical psalm versions, too. Sometimes the music doesn’t fit the words. Check out, for instance, the version of Psalm 88 in the blue Christian Reformed Church Psalter Hymnal, where the darkest Psalm in the Bible is set to light, bouncy music.

* When people think of “chant,” they often think of Gregorian chant. There are forms of Gregorian chant that can be quite powerful (e.g., the ones included in the Cantus Christi), but those aren’t what springs immediately to mind. Instead, when you say the word “chant,” people think of a choir singing Gre-e-e-go-o-o-o-o-o-o-r-r-i-i-a-a-n cha-a-a-a-a-a-a-a-a-a-a-n-n-nt, with every syllable stretched out over a series of notes, rising and falling in a soothing way. That’s great for ambiance, with one candle lit, when you’re having dinner with your wife. But it isn’t warlike and it isn’t something the congregation can sing.

* The Anglican tradition includes a lot of Psalm chanting, but if you get a CD of it, chances are pretty good that it will be sung by a boys’ choir. Now there’s nothing wrong with a bunch of young boys singing in their high-pitched prepubescent voices. But the effect is more sweet than warlike, and such CDs don’t give you a good idea of what chant could be like.

* I mentioned above that I love the Genevan psalms. Sung at a good pace, they’re lively, dancelike, and at the same time warlike. You can imagine pounding your spear on the ground as you sing them. But sung slowly, in a dirgelike fashion, few people can stand them for more than a stanza or two. Ho hum.

And if you buy a CD of Genevan psalms, chances are that’s what you’ll get, perhaps because a choral performance, especially with people singing parts, needs to be slower to bring out the complexity of the music. For that reason, Bach’s motet “Jesu, meine freude” is going to be sung more slowly than the hymn “Jesus, Priceless Treasure.”

The other thing you’ll find on a CD of Genevan psalms (or, worse, in the liturgy!) may be an organist doing improvisation for a while between each stanza. Don’t get me wrong. That kind of stuff is fine — for a concert. My acquaintance Harm Hoeve is a great Dutch organist and he does fantastic improvisations on the Genevan psalms. But it kills congregational singing and it makes it unlikely that the congregation will want to sing more than a couple of stanzas.

So when you listen to CDs of this sort of music, you have to use your imagination. Imagine what the Genevan psalms would sound like if they were kicked up a gear or two and sung by a bunch of David-like soldiers. Imagine that those Anglican chants were being belted out by a bunch of tribal warriors : “Let God arise and let His enemies be scattered.”

Having said all of that, I must also say this: In criticizing these traditions, I’m not saying, “My church does this rightly, but yours doesn’t.” Rather, my aim is to point out something that the whole church, my congregation included, needs to work on. I don’t know of very many churches at all that sing all 150 Psalms, let alone in a good literal translation, let alone in a lively and martial way. What can we do to bring about a change?

Cut-Flower Prayers

So if a minister ought not to be a shopkeeper, aiming at getting more customers to buy the church’s goods, what should he be doing? Eugene Peterson gives three answers: praying, reading (actually: hearing) Scripture, and giving spiritual direction. Working the Angles devotes three chapters to each of those tasks.

When it comes to prayer, Peterson urges caution:

We want life on our conditions, not on God’s conditions Praying puts us at risk of getting involved in God’s conditions. Be slow to pray. Praying most often doesn’t get us what we want but what God wants, something quite at variance with what we conceive to be in our best interests. And when we realize what is going on, it is often too late to go back. Be slow to pray (44).

That may sound odd, but consider Ecclesiastes 5:2: “Do not be rash with your mouth, and let not your heart utter anything hastily before God.” Prayer is dangerous, Peterson maintains, and we should not pray lightly. But so often such light prayers seem to be what people demand of pastors:

One of the indignities to which pastors are routinely subjected is to be approached, as a group of people are gathering for a meeting or a meal, with the request, “Reverend, get things started for us with a little prayer, will ya?” It would be wonderful if we would counter by bellowing William McNamara’s fantasized response: “I will not! There are no little prayers! Prayer enters the lion’s den, brings us before the holy where it is uncertain whether we will come back alive or sane, for ‘it is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of a living God.'”

I am not prescribing rudeness: the bellow does not have to be audible. I am insisting that the pastor who in indolence or ignorance is politely compliant with requests from congregation or community for cut-flower prayers forfeits his … calling. Most of the people we meet, inside and outside the church, think prayers are harmless but necessary starting pistols that shoot blanks and get things going. They suppose that the “real action,” as they call it, is in the “things going” — projects and conventions, plans and performances. It is an outrage and a blasphemy when pastors adjust their practice of prayer to accommodate these inanities (46).

What does Peterson recommend as a remedy? Saturating ourselves in Scripture, and the Psalms in particular, understanding that all of our prayers are responses, second words in response to God’s first words:

What do we do? We do the obvious: we restore prayer to its context in God’s word. Prayer is not something we think up to get God’s attention or enlist his favor. Prayer is answering speech. The first word is God’s word. Prayer is a human word and is never the first word, never the primary word, never the initiating and shaping word simply because we are never first, never primary… (47).

Why Aren’t the Wicked Overthrown?

Another reason the church needs to return to singing the Psalms:

God’s readiness to hear and willingness to grant His people’s prayers are continually proclaimed throughout Scripture (Ps. 9:10; 10:17-18; 18:3; 34:15-17; 37:4-5; 50:14-15; 145:18-19). God has given us numerous examples of imprecatory prayers, showing repeatedly that one aspect of a godly man’s attitude is hatred for God’s enemies and fervent prayer for their downfall and destruction (Ps. 5:10; 10:15; 35:1-8, 22-26; 59:12-13; 68:1-4; 69:22-28; 83; 94; 109; 137:8-9; 139:19-24; 140:6-11). Why then do we not see the overthrow of the wicked in our own time? An important part of the answer is the unwillingness of the modern Church to pray Biblically; and God has assured us: You do not have because you do not ask (James 4:2). —David Chilton, The Days of Vengeance, p. 250.

Video Pastor

In his Slate magazine article, “The Chick-fil-A Church,” Andrew Park talks about the latest megachurch trend:

Most Sunday mornings at Buckhead Church in downtown Atlanta, one person is conspicuously absent: the senior pastor, Andy Stanley. A nationally known evangelist, Stanley is usually 20 minutes away at North Point Community Church, the suburban megachurch he has led for 13 years. To the 6,000 or so faithful at Buckhead, he appears only on video, his digital image projected in front of the congregation in life-sized 3-D. The preacher is a hologram.

I suspect that the trend started with churches that were standing-room only. In many such congregations, the sermon is broadcast into another room in the church building. But with video and hologram technology, the minister’s image can appear in the other room, too. And if in another room, why not on another campus across town? And if there, why not in your town, too? In fact, why not in another part of the world entirely? As Park says, “With video, you just need seats and a screen to replicate the original.”

And why not, someone might ask. The article quotes a man who defends the practice and then sums up his response this way: “If it takes a name-brand preacher to put butts in seats, so be it.” After all, who wants to hear Joe Pastor preach when he could hear someone famous instead, someone like Andy Stanley or Rick Warren?

And wouldn’t it make church planting easier in some ways? You’d need some local staff, but you wouldn’t need to hire a full-time pastor. You’d pay up front for the video machinery, but that would probably be a one-time cost. It wouldn’t be equal to a full-time salary, year after year. And besides, you’d have instant name recognition. “Ever heard of Rick Warren? He’s our pastor,” people could say. Wouldn’t that draw people?

Park writes:

While some people find it strange at first to worship in front of a big screen, they frequently come to view it as no different than attending a service that is totally live, supporters say. And one day, they might be able to relocate to a new town without changing pastors.

So that’s the new trend, and, as the article says, some of these churches may in fact steamroll over other churches, drawing people to the big name and away from the unknown pastors of these other churches. “Forget Rev. Ordinary. My pastor is Rev. Superstar.” It wouldn’t surprise me at all to find this trend catching on.

But Rev. Superstar doesn’t know your name, and you have never met him face to face. Even if he should show up in the flesh some day, you can bet that he won’t come to the hospital when you’re sick. He won’t ever look you right in the eyes as he’s preaching. He’s just a video and you’ll never really get to know him in person. In fact, instead of being a real person to you, a person with a real body, a person who preaching is simply part of his whole-life ministry to you, he’s just flickering lights and recorded words.

Interestingly, Park makes a connection between the attraction to Video Pastor and a certain theology of worship:

To many Christians, though, the sermon is the main event. It’s when all eyes are on the pulpit. It’s when the leader of the church teaches. It’s when the messages in the Bible are distilled for the faithful. Filling that job with piped-in pixels only feeds the celebrity pastor’s star power while creating competition for less-gifted communicators.

“The sermon is the main event.” And if that’s true, then there’s pressure on the pastor to be the superstar preacher. Every sermon ought to be outstanding. And if it’s not, then people will flock to churches pastored by Great Communicators, like Stanley and Warren, people whose preaching they do think is outstanding.

But is the sermon really “the main event”? While Reformed people do sometimes speak of “the primacy of preaching,” the better principle is “the primacy of the Word.” And the Word comes in many forms throughout the liturgy. It comes in the call to worship, in the confession of sin, in the absolution, in the prayers, in the sermon, in the songs, in the benediction. In short, the Word is primary because it shows up in everything and it shapes everything in the liturgy.

If we understand that the Word is what is primary, not the sermon alone, and that the Word comes through the whole liturgy, then it may take some of the pressure away from pastors so that they can preach ordinary sermons instead of feeling that every sermon must be fantastic (“or I’ll lose them to some other pastor, maybe some hologram pastor, who preaches better than I do”).

And that Word comes to us, not simply as words in the air, but as words from the lips of a man who is present with us, a man who has come to us and who lives among us, a man we know, a man who is not necessarily anything special in mself but whose “specialness” is simply due to the office that the Lord has given him.

This also, it seems to me, is important. It is important that the Word be spoken to you by a man you know, by a man who sometimes has bad breath or whose hair gets mussed up, by a man whose hands reach out and shake yours after the service, by a man who puts his arms around you when you’re grieving, by a man who grips your hand as he prays for you when you’re about to go into the operating room, a man whose kids run around after the service and have to be reined in sometimes, a man who sometimes feels discouraged but who pours himself out during the service anyway, a man who doesn’t simply explain Scripture from a distance but also lives it out up close to you.

Sure, that man is weak. He isn’t impressive. He may be a great preacher, but he may also stumble over his words or speak in a bit of a monotone. His preaching may be lively and vigorous and exciting, but it may be at times, even most of the time, somewhat dry. In fact, his preaching and he himself may seem weak and foolish. But that is God’s way of displaying His wisdom and His power: not through Rev. Superstar but through Rev. Ordinary.

[HT: Rick Saenz. More on this trend here.]

Solemnities

Almost a year ago, I quoted a passage from C. S. Lewis on the medieval word solempne and talked about the relevance of what Lewis says for our worship services today. Now here’s Chesterton on much the same subject:

Celebrations need not be any less solemn because they are celebrations. In fact, in the finest parts of our old English poetry and general literature the very word used for a feast is a “solemnity.” The loss of this sense of the solemnity even of a happy festival is one of the most serious losses of our time, one of the most serious gaps in our version of the art of enjoying life. For unless you learn to take joy solemnly you will never learn to take it joyfully. — G. K. Chesterton, “On Long Speeches and Truth,â€Â Collected Works 27: The Illustrated London News 1905-1907, p. 133.

Apparently Chesterton did not think that only a casual celebration, complete with flip flops, shorts, and Hawaiian shirts, could be joyful.  Nor did he think that solemnity was the same thing as gloom. Quite the contrary. The best and highest joy, to Chesterton as to Lewis, was a solemn joy, grand and majestic, and the best and highest celebration was a solemnity.

Kneeling

A parable by Doug Wilson:

There was a certain minister who decided one day, while studying the Scriptures, that an appropriate posture while confessing sin was the posture of kneeling. He raised this as a possibility during a congregational meeting, and suggested that the church look into obtaining kneeling benches.

To his surprise, the opposition to this suggestion was immediate and adamant. The spokesman for the opposition declared that such activities “looked Roman Catholic to him, and as for him and his house, they were not about to get on the road to Rome.”

In response, the minister reached for his Bible and opened it, but to his shock and dismay, he was told to “put that down.”

“We don’t care what you might pull out of there,” the man said. “In our Reformed tradition, we don’t kneel. We are not going back to Rome.”

“Certainly not,” the minister said. “You don’t need to. You are already there.”

Of course, the man was shocked and offended, along with those whose heads had been nodding while he had been speaking. “What do you mean by that?” he snarled.

“Our Protestant forefathers protested against the Roman Catholic church because many of their practices were not biblical. They were told it did not matter, that the tradition of their church determined what they were going to do. You have just summarized this position very nicely.”

The man was at a loss for words, and while he was gaping, the minister continued.

“The Scriptures everywhere testify against this attitude. You don’t care what God says to do. You care what it looks like to others. And when we begin kneeling to confess, this will have to be one of the first sins we must confess.”

Active vs. Liturgical?

Leadership Journal just published the results of a recent survey of American Christians from which, the article says, there emerged “portraits of five distinct segments,” each consisting of about 20% of the total. They named the segments “Active, Professing, Liturgical, Private, and Cultural Christians.”

What strikes me as particularly weird was the inclusion of “Liturgical Christians” as a category distinct from all others. (“Distinct” is their word.) Liturgical Christians, they say, are “predominantly Catholic and Lutheran,” which is already a bit odd since Episcopalians are liturgical, too, to say nothing of some Reformed churches.Â

It’s also very hard for me to believe that Catholics and Lutherans (and Episcopalians) make up only 16% of American Christians. Surely that means that many people in liturgical churches are counted in the other categories. Surely there are people who are members of liturgical churches but who are also what the survey calls Private Christians or Cultural Christians. And surely there are members of liturgical churches who are also Professing Christians and Active Christians.

Liturgical Christians, we’re told, are “regular churchgoers,” have a “high level of spiritual activity, mostly expressed by serving in church and/or community,” and “recognize [the] authority of the church.” But how, then, are they “distinct” from Active Christians or Professing Christians?

It seems fairly likely to me that these segments didn’t actually arise from the results of the survey, as the article claims, but that the surveyers themselves imposed these categories, perhaps through the sorts of questions they asked and the assumptions they brought to the survey.  I suspect that asked questions based on a certain set of assumptions (“This is what constitutes an ‘active Christian'”), but that they found that there were people who didn’t fit into the categories created by those assumptions (“What do we do with these liturgical people? How about we make a new category!”).  But what were those assumptions?

What, in the surveyer’s mind, distinguished these Liturgical Christians from the Christians in the other categories? I imagine the fact that they regularly attend church distinguished them from the people in the Professing, Private, and Cultural Christian categories. And I suspect they weren’t included as “Active Christians” because they didn’t do some of the practices or agree with some of the beliefs that the surveyers thought were necessary for someone to be considered an “Active Christian.” Either that, or they did something or believed something that “Active Christians” don’t.

But which beliefs? Which practices?  Was it that they tended not to be as active in personal Bible reading, though they heard the Word in the liturgy? Was it that they didn’t evangelize (or beat themselves up for not evangelizing) as much as people who ended up in the Active Christian segment? Was it that they didn’t affirm that salvation was through Jesus Christ? Or was it that they recognized the authority of the church, a characteristic which is listed for Liturgical Christians but not (!) for Active Christians?

The survey itself doesn’t seem particularly valuable to me, but its value may be, not only that it reveals that fully 60% of the Christians surveyed don’t seem to be committed to the church, but that it reveals how evangelicals think about liturgical churches.  As someone who is planting a church which is both evangelical and liturgical, it interests me to know that people in the evangelical world see a sharp distinction between “active Christians” and “liturgical Christians.”

Liturgy and Life

Today, Auburn Avenue Presbyterian Church in Monroe, Louisiana, announced the topic and speakers for their upcoming annual Pastors Conference, January 7-9, 2008.

This year our topic is “Liturgy and Life†and the speakers will explore the importance of worship not only for the church but for all of life. What is the role of liturgy in the life of the child of God? Why is the particular order of the service important? What is the relationship between liturgy and pastoral care? How do you bring liturgical reform in a congregation that has been heavily influenced by American, revivalistic Christianity? These and other questions will be addressed by our four main speakers in our conference this year: Dr. Peter Leithart, Pastor Douglas Wilson, Pastor Jeffrey Meyers, and Dr. James Jordan.

It should be a great conference, and the registration cost is very reasonable. I wish I could go, though that doesn’t seem likely at this point.