Category Archive: Literature

Books I Enjoyed Most in 2012

Last year, I must have been exceptionally industrious. I see that I managed to post my list of favorite reads from 2011 already in January 2012. This year, I’m a little behind. But here it is, at last, listed alphabetically by the author’s last name.

* Louis Berkhof & Cornelius Van Til, Foundations of Christian Education. Great essays; often outstanding insights.

* Po Bronson & Ashley Merryman, NurtureShock: New Thinking About Children. Fascinating and very helpful stuff on, e.g., the effect of praise on children, children’s intelligence tests lacking validity, how kids learn to speak, the importance of sleep for children.

* Walter R. Brooks, The Clockwork Twin. Read to kids. The fifth Freddy the Pig novel; some passages had me howling with laughter.

* John Buchan, The Three Hostages. One of my favorite authors.

* G. K. Chesterton, The Collected Works, vol. 27, The Illustrated London News, 1905-1907 and The Defendant. Wonderful essays.

* Elizabeth Coatsworth, Away Goes Sally, Five Bushel Farm, and The Fair American. The first three in a series of books about a young girl in Maine in the late 1790s. Read to Theia and Vance, with much enjoyment.

* Joy Davidman, Smoke on the Mountain: The Ten Commandments in Terms of Today. Insight after insight.

* Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows. A masterpiece.

* Stanley Hauerwas, Carole Bailey Stoneking, Keith G. Meador, and David Cloutier, eds., Growing Old in Christ. Very helpful essays, many of them rich with insights.

* C. J. Hribal, Matty’s Heart and The Clouds in Memphis. Stories that can break your heart.

* Rachel Jankovic, Loving the Little Years: Motherhood in the Trenches. Not just for mothers; I need to read this one every year.

* Walt Kelly, Pogo: Through the Wild Blue Yonder: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, Vol. 1. I grew up reading these in books my parents had collected. It’s great to see them coming out in a nice hardback edition. There has never been another comic strip like Pogo.

* C. S. Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew and The Last Battle. Great stuff … though I’m glad the eschatology Lewis presents for Narnia isn’t the eschatology of Earth.

* C. S. Lewis, Miracles. I remember trying to read this when I was much younger (a teenager?) and not getting very far. Loved it this time through.

* Richard Lischer, Open Secrets. An enjoyable memoir of the first year of a Lutheran pastorate in southern Illinois; some very good passages on pastoral work, including an interesting and helpful chapter on the often positive function of gossip — “speech among the baptized” — in a church community, as it sorts out people and relations and evaluates them.

* Eloise Jarvis McGraw, The Golden Goblet. Read to Theia and Vance at the same time I was teaching Theia about ancient Egypt.

* A. A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner. Read them to the kids … again. There were times I could hardly stop laughing. I ought to read these every year.

* E. Nesbit, The Story of the Treasure Seekers. Hilarious. Why didn’t I read Nesbit when I was a kid? Especially puzzling, given that I loved C. S. Lewis and Edward Eager.

* Patrick O’Brian, The Thirteen Gun Salute, The Nutmeg of Consolation. The thirteenth and fourteenth in a series that never gets stale.

* Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping. Slow but deep.

* P. Andrew Sandlin & John Barach, eds., Obedient Faith: A Festschrift for Norman Shepherd. I first met Norman Shepherd when I was in seminary and he was a member of the board, and it was an honor to be able to edit this volume for him. There are some very good essays in here.

* Lynn Stegner, Because a Fire Was in My Head. Very realistic and very sad.

* Victoria Sweet, God’s Hotel: A Doctor, a Hospital, and a Pilgrimage to the Heart of Medicine. Very interesting account of a doctor at the last almshouse in America and the change from “inefficient” to “efficient” medicine, with some interesting stuff on premodern medicine, medical politics, etc.

* Hilda van Stockum, A Day on Skates. Very enjoyable.

* J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit. Second time through with the kids. Maybe I’ll tackle The Lord of the Rings this year.

* Lars Walker, Erling’s Word. Blogged about it here.

* Laura Ingalls Wilder, These Happy Golden Years. Read to the kids with as much enjoyment myself as they received.

* N. D. Wilson, Leepike Ridge. Had the kids on the edge of their seats a lot of the time. Or their beds. Wherever they were sitting, it was the edge. Someday, they’ll read The Odyssey and remember this story.

* N. T. Wright, The Epistles of Paul to the Colossians and to Philemon: An Introduction and Commentary. I find Wright’s approach to the so-called “Colossian heresy” quite persuasive.

If there’s one thing to learn from this list, I guess, it’s that most of the best books I read last year were the ones I read with the kids.

Hippomania

I know: You would never have dreamed that I would blog about pony books. But I am the father of a girl who loves horses, dreams about horses, thinks about horses instead of math or does math only via horse word problems, and whose attention can be grabbed immediately by seeing the words “horse” or “pony” on the cover of a book. And that explains why, one afternoon, in the midst of reading some literary criticism, I started laughing.

Geoffrey Trease’s Tales Out of School is an opinionated, fun, and often quite insightful survey and critique of young adult fiction up until the 1960s. Along the way, Trease points out certain elements that show up too often in children’s literature and urges authors to try something new instead of trotting out the old.

Have you ever noticed how many twins there are in children’s literature? Trease has. More than that, he has wondered why — and the answer he gives I find entirely convincing: Though the author has probably never even thought about it, he or she likely wanted to have two children — frequently two girls — who are exactly the same age (which means they can’t be non-twin siblings, of course) and who get to share a bedroom or take vacations together (unlike neighbors or friends).

In the midst of surveying what are often called “holiday books” — books that center on activities that take place outside of the school year — Trease again urges authors to greater creativity. Where should an author turn? Well, says Trease, not to the stables, at any rate.

Let me say quickly, before the riding-crops of indignant enthusiasts rain upon my shoulders, that I have nothing against the pony story as such. It is pleasant to see a generation transferring its enthusiasm from high-powered machines to some of the most attractive of the domestic animals…. That the fantasy of possessing a pony (or two, or three) had become something like an obsession in many children’s minds could in those days be seen from any book department. Typical titles were Wish for a Pony, I Wanted a Pony, I Had Two Ponies, Three Ponies and Shannon, A Pony for Jean, Another Pony for Jean, More Ponies for Jean, and (highest bid so far) Six Ponies. The main thing was to get the word into your title — even if, like the ingenious Mary Treadgold, you called your book No Ponies. (The young hippomaniacs knew perfectly well that the ponies would turn up somewhere in the book.) Almost any book, irrespective of quality, was sure of a considerable sale if the title included that magic word. Some children would have demanded Shakespeare’s Richard III if had been put in the right dust-jacket and renamed A Pony for Richard (142).

Imaginative Biographies

In an enjoyable survey and critique of young adult novels, the historical novelist Geoffrey Trease touches on what he calls “imaginative biographies,” those fictionalized accounts of a person’s life in which whole scenes and conversations are invented by the author:

We may feel that the imaginative biographer is a doubtful ally of history when he writes for adults. There has been a great vogue for his books in recent years, for there is a class of intellectual snobs (mainly feminine, it must be pointed out with more candour than chivalry) who declare that they do not waste time on novels but read only biographies and memoirs. Such readers have no interest in footnotes, appendices and authorities. They want dogmatic statement, garnished with salacious innuendo. They are duly catered for. As the late John Palmer said of them, in that masterly life of Moliere, which demonstrates that wit and a respect for truth are not incompatible: “It is a poor biographer who allows himself to be defeated by lack of evidence.” It would not be so bad if these writers would acknowledge, in a foreword to their fancies, that they lack complete omniscience; if they would emulate Froude’s candour, who completed his contribution to Newman’s Lives of the Saints with these words: “I have said all that is known, and indeed a good deal more than is known, about the blessed St Neot” (Tales out of School, 57).

Christian Salt

Yesterday, I quoted John Updike’s marvelous put-down of Paul Tillich’s theology from his book review in Assorted Prose. Also valuable in that collection is Updike’s review of Karl Barth’s Anselm: Fides Quaerens Intellectum and of Denis de Rougemont’s Love in the Western World and Love Declared. His lengthy essay on parody is helpful, too. But here’s something else that stood out, though I’m not done turning it over in my mind yet, let alone express agreement. I present it here for your consideration. It’s from Updike’s “Foreword for Young Readers,” introducing three fairy tales by Oscar Wilde:

These are called fairy stories. Why? The word “fairy” comes from the Latin word fata, which means “one of the Fates.” The Fates were the supreme gods of the Roman world whose architecture survives in post offices and railroad stations, whose language lingers in mottos, and whose soldiers and officials may be glimpsed in the background of the New Testament. In fact, fairies and all such spirits and tiny forest presences are what is left of the gods who were worshipped before Christ.

Imagine a forest, and imagine the forest overswept by an ocean. The forest is drowned; but along the shore twigs and sticks, dwindled and worn and soaked with salty water, are washed up. These bits are fairy stories, and the ocean is the Christian faith that in a thousand years swept over Europe, and the forest is that world of pagan belief that existed before it. So, when you pick up a fairy story, the substance is pagan wood, but the taste and glisten is Christian salt (Assorted Prose, 300-301).

Tobacco, Snuff, and Grog

There are things you don’t find in children’s books written in the last few years. First, a passage from the book I just finished reading to my kids, Arthur Catherall’s Ten Fathoms Deep, an exciting story about a salvage tug boat off the shores of Singapore in the 1940s or so:

“Hudson rolled a cigarette. One thing he had forgotten when he had returned to Singapore was to get in a further supply of cheroots, so he was reduced to smoking native tobacco, and making his own cigarettes” (p. 135).

Second, a page from the great Edward Ardizzone’s Little Tim and the Brave Sea Captain:

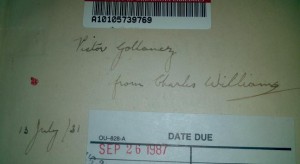

Charles Williams to Victor Gollancz

The other day, I requested a copy of a book by C. S. Lewis’s good friend, Charles Williams. And what did the library end up giving me? Not only a first edition of the book, somewhat frail and held together with a rubber band and stuck in an envelope for safety, but the autographed copy that Williams himself gave to the well-known British publisher, Victor Gollancz.

And they sent this to me, a total stranger, with no idea how trustworthy I might be or (apparently) how valuable the book might be.

Padding or the Point?

I’m the kind of reader who, having once started a book, feels an almost-moral sense of compulsion to finish the book, even if I’m not enjoying it or benefiting from it. But today, I took the plunge. I decided to stop reading a book that I was at least two-thirds of the way through. Yes, part of me insists that it wouldn’t take me long to finish the thing and so maybe I should. But there really isn’t any should about it. Life is short. It’s time to put some books away.

But what was so bad about this book? In a sense, nothing. The book itself was innocuous, a mildly helpful book on the importance of thankfulness, which is certainly a subject I could benefit from. And the book had some good things to say. So why am I giving up on it now?

Because most of the book strikes me as padding. Yes, there are good things here and there, but I have the feeling that they could all have been summed up in, well, a medium-length essay instead of a book. To make the thing book-length, numerous illustrations and stories have been added, a few of which are quite helpful but many of which seem unnecessary.

Here’s an example of the kind of thing I mean, which I’ve made up for this occasion. Suppose an author says something like: “The Christian life is difficult.” Suppose then that the author goes on to tell the story of a classical pianist, tacking an extremely difficult piece. Suppose that story goes on for a page, maybe even two or three pages, describing how the pianist had to practice, how she failed to master the piece, how she had to work at it for years until finally she had trained herself well enough so that, at last, she could play it … and even then found it extremely taxing. All of that to make what point? Well, no point, really. It was all just an illustration of what it means for something to be difficult.

That’s the kind of thing I found in the book I was reading and it’s why I’m closing the covers. It’s padding, not an illustration that really helps make the point.

Erling’s Word

I can’t recall how I discovered him, but I recently read Lars Walker’s first novel, Erling’s Word with great enjoyment. It’s a fantasy novel that comes close to historical fiction: some of the characters were real, including the ruler Erling Skjalgsson, but there are also elements from Norse mythology including the very real (and false) gods. But what I found particularly gripping was not just the twists of the plot but its presentation of the spread of the gospel among the Norse.

Perhaps it doesn’t surprise us that Vikings became Christians, but surely it ought to. Or perhaps we’ve never thought about what that transformation must have involved, not only personally but also socially and politically. Lars Walker has. What he describes ought to remind us that history, including the history of the church, is often very messy. But at the same time, the messiness doesn’t mean that Christ wasn’t at work or that the people involved in that messiness were not, in their own flawed way, striving to be faithful to him.

Perhaps it doesn’t surprise us that Vikings became Christians, but surely it ought to. Or perhaps we’ve never thought about what that transformation must have involved, not only personally but also socially and politically. Lars Walker has. What he describes ought to remind us that history, including the history of the church, is often very messy. But at the same time, the messiness doesn’t mean that Christ wasn’t at work or that the people involved in that messiness were not, in their own flawed way, striving to be faithful to him.

As with Constantine or Charlemagne or Alfred the Great or Brian Boru, so with the Vikings. Rulers who become Christians do not suddenly do everything right. They do not hear the gospel, believe, and then immediately make all the right changes in their public policies and their country’s laws. Nor do they immediately stop their own personal immoralities. We can look back at them and see their flaws and their on-going corruption. But at the same time, we ought to be struck by the courage of, for instance, a ruler who risks the murderous rage of most of his subjects by refusing to dedicate a meeting to the old gods but opens it instead in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. In a time of darkness, Jesus reminds us, “he who is not against you is for you.”

Here’s one passage to whet your appetite, though there are several others that I appreciated so much I had to stop and read them to my wife. In it, the main character, the priest Ailing, who is plagued by doubts (to put it mildly), is speaking to Erling:

“How did you become a Christian, my lord? What keeps you firm? I’ve heard of your king Haakon the Good. He tried to live as a Christian, but the lords made him sacrifice and he was buried as a heathen, they say.”

“We went a-viking in Ireland,” said Erling, “my father and I. I saw a man — a priest — die for Christ. We were holding him and others for ransom, and some of the lads were having a lark and thought it would be sport to make him eat horseflesh. He refused, and the lads took offense at his manner. They tied him to a tree and shot him full of arrows. He died singing a hymn. I thought he was as brave as Hogni, who laughed while Atli cut his heart out. My father said not to talk rot, that a man who dies over what food he’ll eat dies for less than nothing.”

“I’ve never seen a true martyrdom,” I said. “I’ll wager it wasn’t like the pictures.”

“No,” said Erling. “It looked nothing like the pictures in the churches. Martyrs die like other men, bloody and sweaty and pale, and loosening their bowels at the end.”

“So I’d feared.”

“What of it? The pictures are no cheat. Just because I saw no angels, why should I think there were no angels there? Because I didn’t see Christ opening Heaven to receive the priest, how can I say Christ was not there? If someone painted a picture of that priest’s death, and left out the angels and Christ and Heaven opening, he’d not have painted truly. The priest sang as he died. Only he knows what he saw in that hour, but what he saw made him strong.

“I saw a human sacrifice once too, in Sweden. When it was done, and my father had explained how the gods need to see our pain, so they’ll know we aren’t getting above ourselves, I decided I was on the Irish priest’s side.”

“And you’re sure our God doesn’t need to see our pain?”

“Not in the same way. I serve a God who will not have human sacrifice. You’ve never believed in human sacrifice, but I did once, so I can tell you it makes no little difference.”

This is a first novel and there are some flaws, but I highly recommend it, though I’ll add that it doesn’t soft-pedal the sins of its characters, let alone sugarcoat the sins of pagan Norse culture. Erling’s Word has been revised slightly and is now included, together with a second novel that I’m itching to read, in the volume The Year of the Warrior.

Festa More than Fuel

The other day, I was driving somewhere and heard a woman on Christian talk radio explaining her discoveries in relation to dieting. She said that her strategy works like this: We have to go back to the Bible and see what food is for. God created food for fuel. And so for the first several weeks, we want to take the enjoyment out of meals and plan our meals only as fuel for our bodies. After that time, when we have this perspective firmly in our minds, we can begin to add in some of the ingredients that make our food more enjoyable, but the fundamental thing we have to remember is that food is fuel.

Well, who can deny that food is fuel? But is that all food is? Is that all that the Bible tells us about food?

This blog entry is hardly sufficient for a complete biblical theology of food, but notice that in the Bible food is first presented without any reference to fuel at all. It is simply given to Adam and Woman: “See, I have given you every herb that yields seed which is on the face of all the earth, and every tree whose fruit yields seed; to you it shall be for food” (Gen 1:29). I suppose one might argue that God gave the herbs and the fruit to Man and Woman as fuel, but notice that that’s taking a step beyond what is actually said. Yes, fuel is part of what’s in view here, but we cannot conclude that it’s the only thing in view.

Similarly, in Genesis 2, we hear that God filled His Garden with “every tree … that is pleasant to the sight and good for food” (v. 9). Does “good for food” mean that the fruit is good as fuel? Undoubtedly that’s part of it. But notice how the context emphasizes enjoyment: These trees are “pleasant to the sight.” And that suggests that the goodness of their fruit as food includes not just their ability to give us the energy and nutrients we need, but also their ability to give us pleasure as we eat them. Fruit tastes good, and Genesis 2 doesn’t warrant approving the sugars in fruit for their ability to give us energy while disapproving of the way those sugars taste in our mouths.

Jumping ahead in Scripture, we find that food, far from being only fuel, is also reward. After Abram conquers an army of invaders, Melchizedek gives him “bread and wine” (Gen 14:18). In fact, if you want to work this out further, you can think of food (following James Jordan, who has written extensively about this) as Alpha Food, the kind of food that gives you fuel and helps to strengthen you, and Omega Food, the kind of food that gives you rest and pleasure after your labors. Bread is a good Alpha Food: you start the day with bread. But wine is Omega Food: if you try to start the day with a couple of glasses of wine, you’re not going to get to work, but at the end of the day, wine and the relaxation it brings is a good reward. Interestingly, Scripture also tells us to give wine to certain people for comfort (Prov 31:6-7). We shouldn’t think that there’s something bad about “comfort food.”

The use of food in connection with offerings in the Bible teaches us something else about food: Food is communion. Think, in this connection, of how Paul presents the Lord’s Table and the table of demons — that is, the food eaten at the table of the idols. In both cases, communion is taking place as one eats and drinks, either communion with the Lord or communion with the demons who are “behind” the idols. Food is communion: When you eat together, you commune together.

There’s a lot more that could be said about food, but already we see that if we really go back to Scripture to learn about the purpose of food, we won’t conclude that food is merely fuel. Food is also for enjoyment, for rest, for comfort, for reward, for communion. While it may be necessary for some Christians to diet, it seems to me that an approach to dieting that depends on eliminating all these other aspects of food in favor of presenting food only as fuel is wrongheaded.

Around the same time that I heard this advice on the radio, my bedtime reading with my children was Valenti Angelo’s The Hill of Little Miracles, which contains some great passages about food, passage like this one, describing the festa after the main character’s little sister is baptized. The Italian family is gathered around the table when the Irish policeman stops by:

The group shouted with joy when a huge platter of rice, cooked to a golden brown in a rich sauce of olive oil, mushrooms, tomatoes, chopped onions, and chicken livers, was brought in. Soon after that, a large round platter of fritto misto, a mixture of chicken, zucchini, celery, young artichokes, eggplant, all fried in egg batter, took the place of honor on the table. So Patrick stayed a little longer, just to praise Mamma Santo’s fritto misto. Incidentally he washed the fritto misto down with another glass of zinfandel. The Santo house was filled with friendliness, and everyone praised and enjoyed the good food….

Papa Santo sang happily as he went down into the cellar. He returned with three bottles of wine. And Patrick stayed just a little longer. The fritto misto had disappeared. The salad was brought in. Romaine lettuce with chopped red onions, sliced tomatoes, stalks of young celery, sprinkled with black olives and fillets of anchovies, with dressing of olive oil mixed with vinegar and garlic. After each plate was scraped clean of chicken bones, everyone took a large helping. Salami and soft white cheese, called Monterey cream cheese, was placed on the table. A ponderous pot of black coffee sent out a steady thin stream of steam from its spout (49-50, 51-52).

Now, isn’t that a good and biblical way of looking at food? Loads of it, tasting good, with family and friends all rejoicing around the table. I suppose that I shouldn’t have been surprised when I finished the chapter and turned out the light, only to hear my kids say, “I’m hungry!” (Incidentally, a lot of the great books for children in the past were full of glowing descriptions of food, and the best essay on the subject can be found in Annis Duff’s “Bequest of Wings.”)

Family Chamber Music Societies

Successful family living strikes me as being in many ways rather like playing chamber music. Each member of the ensemble has his own skills, his own special knack with the part he chooses to play; but the grace and strength and sweetness of the performance come from everyone’s willingness to subordinate individual virtuosity and personal ambition to the requirements of balance and blend.

The great difference between ensemble playing and ensemble living is that for the one you have a prescribed pattern that shows you where to come in and how to weave your own part in and out among the intricacies of the other players’ notes; when to take the leading part, and when to twitter away quietly in the background. But living together is a perpetual exercise in improvization. Most of us senior members of family chamber music societies have some idea of what the general form and finish of the composition should be — heaven help us if we have not! But we direct the proceedings without rehearsal, and with players who are feeling their way, sometimes timidly and sometimes with comical forthrightness, through the unwritten score.

Not for us is the satisfaction of retrieving our errors as actual players do, with, “Let’s take that passage over again and this time do it right.” What’s gone is gone, and the worst of our case is that sometimes in the surge and press of our performance we are not even aware of the nature of our mistakes and are troubled by discords that we are powerless to remedy. We can only play resolutely on, hoping that by practice we shall learn to execute similar passages with skill and assurance and so, perhaps, make amends for our earlier blunders. Nor is there any counterpart in our experience of that other prerogative of real ensemble players: never on coming to the end of a beautifully played movement can we exclaim, “That was marvelous! Let’s do it again!” Families can never count on repeating the joys of success: they can only remember. — Annis Duff, “Longer Flight”: A Family Grows Up with Books, 11-12.

Updike and Schmemann

In the “I know you don’t care about this at all, but it interested me, for whatever it’s worth” department, apparently John Updike read Alexander Schmemann’s For the Life of the World. In a book review of Still, a recent memoir by Lauren Winner (which I haven’t read, by the way), I came upon this paragraph:

She stumbles on a scribble in a copy of For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy, by the Orthodox writer Alexander Schmemann, that belonged to late novelist John Updike. In the margins, Updike had penciled “God gives us many gifts, but God is He Who gives God,” a quote from Augustine.

Books I Enjoyed Most in 2011

Here’s my annual list of the books I enjoyed most in 2011, listed alphabetically by the author’s last name. Enjoy!

* Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart, No Longer at Ease, and Arrow of God (all three available in one volume now). Great novels by a Nigerian novelist. The first, especially, should not be missed for its presentation of the effects of the gospel and of the way in which it was presented on prechristian Nigerian culture.

* Esther Averill, Jenny and the Cat Club and its sequels, in particular, The Hotel Cat and Captains of the City Streets (which is actually a prequel). I read these to my kids and they enjoyed them.

* Jeffrey Barlough, Dark Sleeper. Okay, the ending was a bit weak, I thought, but I forgive it easily for the atmosphere, the great writing, the many laughs, and the Blaylockian love of good food and pints of porter in cozy inns with the cold and fog outside. Tim Powers recommended the book and I agree with him: “When you’ve finished you’ll want to go back again soon.”

* Owen Barfield’s The Silver Trumpet. I don’t know how much of Barfield’s unique philosophy is present in this fairy tale; someday I’ll read some of Barfield’s nonfiction and perhaps I’ll discover that I already understand what he’s saying because I read this one first. But I read it with my kids as a fun story. Tolkien’s kids loved it, and so did mine.

* Ruth Beechick, Adam and His Kin. Very interesting. She’s wrong on a lot of points (e.g., dispensationalism, demons marrying humans in Genesis 6, drawing on Hislop’s The Two Babylons). So why did I enjoy this book? Because she takes the biblical chronology seriously. We need something like this, drawing on the work that Jim Jordan has done on biblical chronology, etc., and without the weird stuff Beechick throws in. I’ll add that I also very much enjoyed her The Language Wars and Other Writings for Homeschoolers, which includes balanced and helpful essays on phonics (and the erroneous claim that it can solve all reading problems), the teaching of history (following biblical chronology), how homeschooling magazines choose their articles and review books (often based on who advertises in the magazine), and more.

* Wendell Berry’s The Memory of Old Jack. Very well done.

* James P. Blaylock, The Digging Leviathan. What a strange but enjoyable book. Laughed out loud at points. Can’t even begin to describe it.

* Walter R. Brooks, The Story of Freginald. The fourth Freddy the Pig book. Lots of fun.

* Bo Caldwell, The Distant Land of My Father. Reads like a memoir, to the extent that it was hard to imagine that the author wasn’t writing about her own life; very enjoyable.

* Bruce Campbell, The Secret of Skeleton Island. Okay, this isn’t what you expected me to read this year. I understand that. Yes, this is a boy’s adventure novel, written back in the ’40s, the first in a series of novels starring Ken Holt. I hadn’t read any of the Ken Holt novels when I was a boy, but they were the kind of stuff that I gobbled up. I came across a reference to these books online, identifying them as one of the greatest and best written of the old “series books,” so I decided to give this one a try. Loads of fun for your inner boy.

* Milton Caniff, The Complete Terry and the Pirates, 1934-1936. Lots of fun; early comic strips by one of the great cartoonists.

* Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. Compelling: Carr argues that the internet — and especially Google, social media, and hyperlinks — are a “technology of distraction,” requiring constant decision making (click this link or not?) and thereby exercise our brains in such a way that the decision-making areas of our brains develop while our ability to read, concentrate, be attentive, think deeply, and exercise empathy and compassion deteriorate so that our thinking becomes shallow. Lots of interesting stuff here about neuroplasticity, computers, and more. Is it accurate? The more I surf the web, the more I‘m persuaded.

* Rebecca Caudill, Happy Little Family, Schoolhouse in the Woods, Up and Down the River, and Schoolroom in the Parlor. Read this series to my children, who enjoyed it immensely.

* G. K. Chesterton, The Man Who Was Thursday. What can I say? This is a great book, but it’s not one that I fully understand.

* Joan Chittester, The Gift of Years: Growing Old Gracefully. Not my usual fare. The author’s theological stance is quite different from my own. But there’s some great stuff here, mixed with some junk. Chew carefully and spit out the bones.

* Clay Clarkson, Heartfelt Discipline: The Gentle Art of Training and Guiding Your Children. I do not necessarily agree with everything Clarkson says. In particular, his treatment of the “rod” in Scripture needs careful evaluation. But it’s one of the best treatments of wholistic discipline I’ve come across, and the only one I’ve seen yet that deals with, e.g., sympathy as part of discipline.

* Sally Clarkson, The Mission of Motherhood: Touching Your Child’s Heart for Eternity. I didn’t agree with everything and found some things in the book a bit sentimental, but there’s a lot of good stuff here about raising children and about the attitude parents — and not just mothers — need.

* Barbara Cooney, Miss Rumphuis. What list of great books would be complete without some picture books? This is a particularly beautiful one.

* Meindert DeJong, The Wheel on the School. One of the great things about being a dad is getting to read to your kids, and one of the great things about that is that you can read old favorites. But another great thing about it is that you can read books you missed when you were a kid. For some reason, I never read DeJong, classic those his books are. I’m making up for that now. My children and I loved this one.

* August Derleth, The Moon Tenders and The Mill Creek Irregulars: Special Detectives. Remember how I sounded almost defensive when I talked about reading the Bruce Campbell novel above? Well, these are the first two of another series of boy’s books, perhaps the best written such series ever, and so there’s no need for me to sound defensive here. These books are simply wonderful, not so much for the plots, which meander enjoyably but for the historic details, the atmosphere, the sense of place, the recollection of a boyhood in Wisconsin in the ’20s. The whole set is available here, and I think I’ll start saving my pennies to buy it.

* Eilis Dillon, A Family of Foxes and The Sea Wall. I had never heard of this author before last year and had never read anything by her when I was growing up, more’s the pity. I read these two to my children, who loved them. Excellent writing, great adventures.

* David Hackett Fischer, Growing Old in America. The author’s suggestions at the end are weak, but the book is very, very helpful in understanding the “deep change” that took place with regard to the American attitude toward the elderly and the shift to a “cult of youth.”

* Tim Gautreaux, The Next Step in the Dance. Gautreaux is a very good Cajun writer.

* Charles Boardman Hawes, The Great Quest. Reminded me a lot of Robert Louis Stevenson.

* Thomas Howard, The Novels of Charles Williams. Don’t venture into the deep waters of Williams without this guidebook. In fact, the guidebook would be great reading even if you weren’t reading Williams. There is so much here about Williams’s themes: self-sacrifice, our mutual dependence, the symbolical nature of everything in life, the glory of hierarchy, the demand of faith in every small decision — I could go on and on.

* James B. Jordan, Judges: A Practical and Theological Commentary. At the risk of being accused of overstatement, I will say this: This is the only really good commentary on Judges. Sure, it could be improved. Jordan himself has written more about Judges since this commentary, and the commentary was written before Jordan really understood chiasms so he says nothing here about the chiasm that structures the book.

But even though there is some helpful stuff in many other commentaries, none of them come close to this one. Why not? For one thing, none of them deal much with the symbolism of Judges. Look, there are easier ways of setting a Philistine field on fire than catching three hundred foxes and tying them tail to tail with a torch between each pair. But that’s what Samson did. In fact, many of Samson’s actions are full of symbolism, but most commentaries do little to nothing with that symbolism.

Perhaps that’s because they think of Samson as wicked or stupid or both. And that’s another problem that’s widespread in commentaries on Judges. Most do not regard the judges as men of faith. Daniel Block, for instance, helpful though he is for Hebrew stuff, refuses to let Hebrews 11 influence his reading of the judges and ends up seeing almost all of them as compromised or faulty or even wicked in some way, so that the message of Judges becomes that God saves His people not just through the judge but actually more in spite of the judge.

I see, by the way, that George Schwab has a new commentary on Judges (Right in Their Own Eyes: The Gospel According to Judges). The link will take you to the opening pages of the book, including the introduction, which has some good things in his introduction about Samson and the honey in the lion but … I can tell by the chapter titles where he’s going. The chapter on Ehud is entitled “Soiled Southpaw, Rotund Ruler.” Ehud soiled? In what way? Perhaps, like Block, Schwab thinks that Ehud shouldn’t have assassinated Eglon, but that’s simply wrong. In any case, it seems to me that it was Eglon who was soiled — who, in fact, soiled himself — and that Israel was meant to laugh about it as they read the story. But keep reading Schwab’s chapter titles: The one on Barak calls him a “sissy,” the one on Jephthah speaks of him as jaundiced (whatever that could mean). Sigh.

If you want commentary recommendations on Judges, here are mine: Start with Jordan, supplemented with his other essays and lectures on Judges (e.g., “Samson the Bridegroom”). Move on to Davis for a few more insights and perhaps use Block for some help with the Hebrew. But you’re not going to find too many other people who approach Judges the way Jordan does, and that’s too bad.

* Jan Karon, At Home in Mitford. Rereading this series. Sure, there are some overly sweet and sentimental parts, but on the whole I’m enjoying it.

* Frank O. King, Walt and Skeezix: 1923 & 1924. Old enough to remember the comic strip Gasoline Alley? I’m not. But I love these old strips, especially because little Skeezix reminds me of my son.

* Eleanor Frances Lattimore, More About Little Pear. The fourth and final volume in a series that my children and I enjoyed.

* C. S. Lewis & E. M. W. Tillyard, The Personal Heresy: A Controversy. High quality debate. Just when you think Lewis has won, you read Tillyard’s contribution. It’s great to see men of this caliber disagreeing with each other and working out their similarities and differences in the course of this debate. In the end, I think Lewis wins, but Tillyard’s essays, too, are worthwhile reading.

* C. S. Lewis, The Silver Chair and The Horse and His Boy. I’m reading these to my children. I knew I’d enjoy them, but I had forgotten how good the Narnia books really are.

* George MacDonald, David Elginbrod. Odd theology throughout, though worth carefully thinking through because MacDonald often forces us to confront how we present our doctrine and how some wrong presentations become entrenched and do great damage (e.g., when people say that God doesn’t see as “as we really are” but sees us only in Christ, that can lead to the conclusion that God doesn’t really like us but simply tolerates us for Christ’s sake).

* Jack McDevitt, Seeker. The third in McDevitt’s novels about Alex Benedict. Very well crafted science fiction.

* Patrick O’Brian, The Surgeon’s Mate, The Ionian Mission, Treason’s Harbour, The Far Side of the World, The Reverse of the Medal, and The Letter of Marque. Not a weak novel in the series yet. My neighbor in Oregon read straight through the entire series with barely a pause and when I asked him if it didn’t start to get repetitious, he assured me that it did not. He’s been right so far!

* Les & Leslie Parrott, Saving Your Marriage Before It Starts. Quite helpful. I drew on this for my premarital counseling this year.

* Rousas John Rushdoony, Intellectual Schizophrenia: Culture, Crisis and Education. Some stuff wrongheaded — e.g., family as the central institution; parochial schools necessarily bad — but lots of good stuff. It was interesting to discover stuff in this early Rushdoony book that I associate with and learned from later writers. Rush was talking about it all the way back in 1961!

* C. S. Spurgeon, The Complete John Ploughman: John Ploughman’s Talk and John Ploughman’s Pictures. Great stuff, full of rich language.

* James Thurbur, The 13 Clocks. Wonderful fun.

* Cornelius Van Til, Psychology of Religion. There are books I want to read and books I want to have read, and Van Til usually falls into the latter category. This book isn’t particularly fun reading, but what made me appreciate it were the occasional flashes of great brilliance, such as Van Til’s obliteration of the exaltation of reason over emotion or any other faculty.

* H. Gilbert Welch, Lisa M. Schwartz, and Steven Wolshin, Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. One of the most important books I read this year and one which I highly recommend. Welch, et al., argue (convincingly) that most “preventative” testing is unnecessary, along the way showing how pharmaceutical companies affect the “numbers” — e.g., acceptable vs. dangerous cholesterol levels — so that more people are diagnosed as being in a danger zone than before and warning about the dangers of proceeding with treatment based on an overdiagnosis. If you enjoyed Rob Maddox’s lectures at the recent Auburn Avenue Pastors Conference or wanted to know more about the kinds of things he was saying when he talked about the hubris of medicine, check out this book.

* Laura Ingalls Wilder, The Long Winter and Little Town on the Prairie. Read these books as a subversion of Pa’s individualism. The West wasn’t settled by rugged individuals, try as Pa will to be one, but by people banding together, forming towns, helping each other in crises.

* Charles Williams, Descent into Hell. Weird and wonderful.

* Gene Wolfe, The Sorcerer’s House. Perhaps one of the easier Wolfe novels to understand, but it left me turning over this and that and the other thing in my mind afterwards, which is half the fun of reading Wolfe (“Wait a minute! If he said that, then …?!”).