Category Archive: Literature

Lewis on Reading Old Books

Here’s something from a letter, dated October 18, 1919, from C. S. Lewis to his friend Arthur Greeves:

I am not very fond of Euripedes’ Media: but as regards the underworking of the possibilities which you mention, you must remember that the translation has to be rather stiff — tied by the double chains of fidelity to the original and the demands of its own metres, it cannot have the freedom and therefore cannot have the passion of the real thing. As well, even in reading the Greek we must miss a lot. We call it “statuesque” and “restrained” because at the distance of 2500 years we cannot catch the subtler points — the associations of a word, the homeliness of some phrazes [sic] and the unexpected strangeness of others. All this we, as foreigners, don’t see — and are therefore inclined to assume that it wasn’t there. — C. S. Lewis, Collected Letters, 1:467-368.

What Lewis says here may be obvious, but it jumped out at me in this letter as it hadn’t before.  We must miss a lot of allusions and subtle hints, a lot of surprises and a lot of the richness of ancient literature. Perhaps we think some things are strikingly beautiful when the original audience would have found them rather dull, or vice versa. Perhaps we think that a conversation in an ancient play is straightforward when an ancient audience would have been able to “read between the lines” and hear how that superficially straightforward conversation operates on several levels at once.

What Lewis writes about here is part of the challenge we face as interpreters of the Bible, too. We read passages and they mean very little to us, or we conclude that their meaning is very slight and all on the surface, in part because we’re reading these passages thousands of years after they were written.

So, for instance, we read the line in Exodus 15:27 — “Then they came to Elim, where there were twelve wells of water and seventy palm trees; so they camped there by the water” — and we think that Moses must have suddenly felt the urge to provide a bit of color, a bit of description. Or, at most, perhaps he’s simply emphasizing how well the Lord provided for Israel after the hardships at Marah. But that’s it. Most commentaries simply skim over this verse or provide a pious comment (which is not wrong) about God’s provision. If we’re reading the text as people of our own day, this verse means little to us.

But to someone who was steeped in the Scriptures, the references to twelve and seventy, to trees and water, would stand out. He might see those twelve springs of water as a symbolic reference to the twelve tribes of Israel, for instance, and the seventy palm trees as a reference to the seventy nations of the world (Gen. 10). He might think about the connotations of water and trees, going back to the Garden (Gen. 2). His imagination, shaped by the Scriptures, might run forward to the Temple with its bronze sea and garden imagery, to Ezekiel 47 where the water flows out to the world, to Revelation 22, and so forth.

Here’s another example. When Mark starts his Gospel, he writes, “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.” We read through that verse and barely notice the words. But all of the words are significant. What’s the “gospel” here?  Reading this verse superficially, we might think that it’s a reference to the book Mark is writing. Or we might take it simply as referring to how the good news about Jesus began with the coming of John the Baptist.

But if we were steeped in the Scriptures, we might think back to the prophecies of Isaiah where “good news” is proclaimed (e.g., Isaiah 40), which is, in particular, the good news that Yahweh is returning to rescue and rule His people. And if we were citizens of the Roman empire, as Mark’s original readers were, there might be another connotation, as well.  A “gospel” was the announcement of the birth or the victory or the rise to power of an emperor. Mark’s Gospel is a “gospel” in the Isaiah 40 sense, but it’s also a “gospel” in this Greco-Roman sense, since it is the story of the coming of the King.  But it’s easy for us to miss those connotations.Â

What Lewis writes may incline us to give up: We can’t understand all the meanings of words, the subtle allusions that a contemporary of Euripedes would have caught, and so forth, and therefore our understanding and appreciation of ancient literature (including the Bible) are always diminished.

I don’t believe that’s necessarily true of the Bible, though. Perhaps we will struggle to understand some things. Perhaps certain words won’t jump out at us the way they would to, say, Mark’s contemporaries. But I do believe that God has given us enough to understand His Word. That isn’t true of Euripedes, but it is true of Scripture.

We may learn new things as we study the ancient world, and that may help us understand Scripture. There are words we can’t translate because they appear only once in the Hebrew Bible. For now, we make intelligent guesses.  But maybe someday we’ll discover something that helps us get the right translation of those words. But we still know enough to understand God’s Word.

But what is most important is that we be saturated in Scripture so that we catch more of the allusions, so that we know the flow of the story, and so forth. Will we ever fathom all of Scripture’s depths? No. Will our understanding always be that of foreigners who can’t grasp the richness of the story? Perhaps in some sense. But not in another. Scripture wasn’t addressed simply and solely to people of one generation. It was addressed to us also, and if we are followers of the Word then nothing in the Word can be completely foreign to us.

Books I Enjoyed Most in 2007

As is my custom on this blog, here’s a list of the books I particularly enjoyed this past year. The list is in alphabetical order.

* Edward Ardizzone, Little Tim and the Brave Sea Captain. This is a great children’s story, which I’ve read to Aletheia … well, I read the whole thing through only once and I’m pretty sure I was the only one awake at the end. I’ve read the start of it to her several times, but she’s usually asleep by the first few pages (or maybe even before I begin), which suits me just fine. Still, I’ve enjoyed the story and the art a lot. Great stuff!

* Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice. I’ve read this one before, but this time I’m reading Austen in connection with Peter Leithart’s excellent Miniatures and Morals. And in case you’re wondering, real men do read Austen, which is the title of Leithart’s introduction. I blogged about it here.

* Lundy Bancroft, Why Does He Do That? Inside the Minds of Angry and Controlling Men.  Bancroft argues forcefully and persuasively against a number of views about why men become abusive, many of which are likely views you’ve heard. He has worked extensively with abusive men, and so he has good insight into their behavior. Bancroft argues that abusiveness has nothing to do with “losing control” or an inability to communicate well. Instead, he says that the roots of abuse are possessiveness and a desire to control someone else. In other words, the problem is not losing control of himself; the problem is trying to gain control of someone else. Bancroft isn’t writing from a biblical perspective, but his work is helpful pastorally (not to mention personally) because he doesn’t soft-pedal sin or put up with excuses, especially ones clothed in psychobabble.

* Wendell Berry, The Hidden Wound and The Long-Legged House. Very thoughtful essays, the first focusing on racism and its impact, not so much on the black community but on the whites who perpetuated it, and the second mainly on the importance of place.

* Ray Bradbury, Something Wicked This Way Comes. A great novel for the end of October. At times, Bradbury’s language may be overly rich; you can overdose on the purple prose. But it’s a magical novel all the same.

* John Buchan, Huntingtower. This novel is always associated in my mind with a rather dark period in my life when I was feeling lethargic and depressed. Huntingtower was springtime and light and a return to joy for me. It’s still a bracing book.

* Raymond Chandler, Farewell, My Lovely. The second of Chandler’s novels about Philip Marlowe, the private investigator. The plot is good, but the metaphors are gloriously fun.Â

* Joy Chant, Red Moon and Black Mountain. A fantasy novel that starts out as a children’s novel (one might think) but rapidly becomes much more grown-up. There were elements I didn’t care for and parts of the book that seemed a little slow to me, but on the whole it’s a good book.

* Agatha Christie, The A. B. C. Murders. I thought I knew, from a previous reading, how this book ended. Some time back, I started a different Agatha Christie novel only to discover that the twist I had thought belonged to The A. B. C. Murders actually took place in this other novel. Which meant that I had no idea how The A. B. C. Murders actually turned out. Well, it turned out to be one of the most interesting Christie novels I’ve read recently and I enjoyed it thoroughly.

* Jack DeJong, ed. Bound Yet Free: Readings in Reformed Church Polity. This isn’t the most exciting read and not all the essays are well written (or, perhaps, well translated). Still, it’s the only thing out there that collects important writings in the church polity of the Doleantie and I found several of the essays stimulating.

* Brian Doyle, Leaping: Revelations and Epiphanies. A very fun collection of essays. See my comments about this book elsewhere on the blog, specifically here and here.

* Glenn Greenwald, How Would a Patriot Act? Defending American Values from a President Run Amok. The most disturbing book I read this year. Greenwald points out how President Bush deliberately instructed the NSA to ignore the laws passed by congress concerning eavesdropping and then digs into the philosophy that undergirds that disregard for the law, namely the view that the president is above the law. Along the way, Greenwald also talks about US involvement in torture and about the practice of detaining US citizens suspected of terrorist involvement for indefinite periods of time without charges or the chance of a trial.

* Eric Hoffer, The Ordeal of Change. A very interesting collection of essays. I was particularly struck by … well, several things, some of which I’ve blogged. But one of the things that I didn’t blog about was this: Hoffer points out how, in some cultures, especially in the past, inventions and technological developments were seen as toys. The Chinese had gunpowder, for instance, but they didn’t use it for anything productive; they used it for fireworks. Often creativity starts out as play, it seems, and only later settles down to productive use.

* Peter Hopkirk, Like Hidden Fire: The Plot to Bring Down the British Empire. I’ve read John Buchan’s novel Greenmantle more than once, and probably thought that it was entirely fictional. When I included Greenmantle on my list of favorite books a couple years ago, Paul Baxter told me I should read this one. Like Hidden Fire is the true story underlying Greenmantle, the story of how the Germans in World War I tried to unite the Muslim world against the British. A very enjoyable read, with characters here that could have come straight from Buchan.

* Thomas Howard, Hallowed Be This House. If you’ve read Doug Wilson’s My Life for Yours, you may remember that he says he got the idea for his book from this one. In fact, he got the title from this one, too. Howard goes through the house and meditates on the various things that make up a house, the doors, the front hall, the living room, the kitchen, and so on, frequently stressing, in the line that became Wilson’s title, that our lives are meant to be lived sacrificially, that we are to pour ourselves out for one another, and that even the structure of our homes bears witness to this purpose. Well worth reading.

* James B. Jordan, Crisis, Opportunity, and the Christian Future and Trees and Thorns: Studies in Genesis 2-4. The first of these two books is a short booklet, but don’t let its size fool you. Crisis says a lot in a few pages. Along the way, Jordan talks about the progress from Father to Son/Brother to Spirit in Scripture, about the development in Western Civilization from tribes to kingdoms to empires, about the church’s calling in the present day, and a whole lot more. Mind-stretching stuff.

No less important is Trees and Thorns, which is a collection of essays, originally sent out monthly to supporters of Biblical Horizons, on Genesis 2-4. There are load and loads (and loads!) of important insight into these passages of Scripture here. I preached on Genesis 1-4 this past year, and owe many of the things that I said to Jordan.

* Garret Keizer, A Dresser of Sycamore Trees: The Finding of a Ministry. An often fascinating book by a laypastor in Vermon about his calling and his work. There were a number of points where I disagreed with his views on things, but I found myself challenged and encouraged by so many things in this book that it made my list of favorites.

* Ursula K. LeGuin, Planet of Exile. This is the first (and only) LeGuin book I’ve read, and it’s probably not her best. Still, I found her writing compelling and beautiful and I’ll be reading more by her in the future.

* Peter J. Leithart, A Great Mystery: Fourteen Wedding Sermons. This is a great collection of wedding sermons, including the sermon that Leithart preached for my own wedding. But don’t be misled. These aren’t your simple “Love each other” sermons. There’s a lot of meat here, a lot of things worth pondering. And the one he preached for Moriah and me is probably the only wedding sermon you’ve ever encountered that referred to cannibalism. There. Now you have to read it.

* Peter J. Leithart, The Kingdom and the Power: Rediscovering the Centrality of the Church. I reread this book a few months ago and was surprised to see how many things I thought were just coming into discussion now were already published here years ago. There wasn’t a lot that was new to me this time through, but I did very much appreciate the whole book.

* C. S. Lewis, Perelandra and A Preface to Paradise Lost. I read Preface first, and I’ve been quoting it on this blog ever since. Don’t assume that you have to be interested in Paradise Lost to appreciate this book; there’s a lot of stuff here about worship, reverence, respect, hierarchy, nobility, and a host of other subjects that you don’t want to miss. Perelandra is related in some ways to Paradise Lost, being a story about a paradise which isn’t lost yet, and I was interested to see how some of the themes in Preface were worked out in story form here. This is the second of Lewis’s science fiction-ish novels.

* C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters. I read this early in the year and loved it. There are profound things on every page and often in every paragraph. I’ve quoted a few on this blog, but the temptation is to keep quoting and quoting. To satisfy that impulse, I’ve been reading a couple of these letters each week at our Bible study, a practice I highly recommend.

* Arnold Lobel, Days with Frog and Toad and Frog and Toad Together. More books I’ve read to Aletheia. In fact, I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve read these. The other two books about Frog and Toad are good, too, but they don’t quite come up to the level of these ones. The story “Cookies” in Frog and Toad Together is simply outstanding, as is “Alone” in Days with Frog and Toad.

* Thomas Lynch, The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade. Who would have thought that a bunch of essays by an undertaker would be so interesting? Not me, but I’m glad that I saw this author mentioned (by Byron Borger at Hearts and Minds) and picked the book up.

* Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran. Maybe this doesn’t look like something you’d be interested in. After all, the title refers to a novel that you may view with suspicion (Lolita) and the book is about a book club. Ho hum?

Well, the book certainly isn’t for everyone, but I enjoyed it a lot. I very much appreciated Nafisi’s discussion of Lolita, Pride and Prejudice, The Great Gatsby, and a few other novels, and her discussion of Lolita may overturn whatever ideas you had about the novel. But even more important was her description of the changes that took place in Iran after the Islamic Revolution and how they affected people, and women in particular.

* Patrick O’Brian, The Mauritius Command. Another in O’Brian’s wonderful series about Captain Jack Aubrey and Doctor Stephen Maturin. Brilliant writing, a great plot, lots of humor mixed with some sorrow. Beautiful.

* Brendan O’Donnell, Rain from a Rainless Sky: A Work of Theological Botany. This was Brendan’s thesis at New St. Andrews, and it’s well worth perusing. All of creation is symbolic; all of it is designed by God to teach us something. So what are we to learn from sagebrush?

* Stormie Omartian, The Power of a Praying Husband. “What?” you say. “I see this book and all the variants of it (Power of a Praying Wife, Power of a Praying Mother, Power of a Praying Parent, Power of a Praying Dog-sitter … oh, I just made that up) all over the place. It’s some charismatic book, isn’t it? What’s it doing on your list of best books?”

But it really was one of the best things I read this year. I picked it up because a friend of mine, Rich Bledsoe, recommended it as one of the most helpful things for a marriage. Which is simply to say that thoughtful prayer is one of the most helpful things for a marriage. Most of us, however, aren’t good at thoughtful prayer. If I were to ask you what your wife needs prayer for, you could probably think of a few things. But what Omartian has done is think of a lot of things, grouped into twenty categories. She provides some discussion, a few Bible verses, and sample prayers.

Yes, there’s some stuff here that seems weird to me. At times, in the middle of the prayer, she has the pray-er addressing his wife (“And to my wife, I say…”), which seems very strange to me in the context of a prayer to God and which strikes me as something I’ve encountered only in charismatic circles. But ignore that. Ignore all the weird stuff here. The book is still worthwhile simply because it will help you pray for areas of your wife’s life and for needs your wife has that you have never noticed or thought about. And that’s valuable.

Sure, you could have written a similar book if you’d thought of it. Sure, someone like Doug Wilson might have been able to write an even better book of prayers. But you didn’t and neither did Doug. Stormie Omartian did (and a host of similar books which are all probably just as helpful), and so we should say “Thank you.”

* Gervase Phinn, The Other Side of the Dale. Fun stuff. Like James Herriot, only about a school inspector in England.

* Walker Percy, The Second Coming. What can I say about this one? I enjoyed this novel, understood large parts of it, and need to read it again sometime.

* J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. The last three of the series. Darker than the previous volumes, these books show that the series is definitely not (or not just) “kid’s fiction.” They also make clear what Rowling hinted at from the beginning, namely that she was writing with a Christian framework in mind. I enjoyed them very, very much.

* Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, I Am An Impure Thinker. Dense, challenging, and fascinating essays. They’ll change your whole way of thinking.

* Gene Wolfe, The Wizard Knight (published as The Knight and The Wizard). Great fantasy novels which are, at the same time, schools of wisdom, all about maturation and what it takes to be a man, a knight, and a king. Wolfe is one of my favorite writers. Worth reading again and again.

* N. D. Wilson, Leepike Ridge. A fun adventure novel.

* Sara Zarr, Story of a Girl. An excellent young adult novel by a Christian writer. Moriah and I both read this in one weekend and we talked and talked about it afterwards.

Angela’s Ashes

I picked up a copy of Frank McCourt’s memoir Angela’s Ashes some time ago and have had it sitting on the shelf until recently. I’m about twenty pages from the end right now, and I’m sorting through what I think about it.

The book won the Pulitzer Prize in memoirs and received high praise from a lot of people, and I can see why. McCourt writes fairly well, there’s a lot of humor in the book, and the story he tells is interesting. It’s largely the account of his childhood in Limerick in the 1930s and ’40s as the son of a man from Northern Ireland who was given more to drinking his pint or twenty than to bringing home the wages and caring for his family.  The second and third paragraphs sum the book up fairly well:

When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I survived at all. It was, of course, a miserable childhood: the happy childhood is hardly worth your while. Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood.

People everywhere brag and wimper about the woes of their early years, but nothing can compare with the Irish version: the poverty; the shiftless loquacious alcoholic father; the pious defeated mother moaning by the fire; pompous priests; bullying schoolmasters; the English and the terrible things they did to us for eight hundred long years (p. 11).

There are passages that are heartbreaking, and throughout you have McCourt’s distinctively Irish voice. He writes so that you can hear the accent.

And yet I wonder….

My own memories of my childhood are sparse, perhaps unusually so. I remember certain events vividly, but there aren’t many of those memories. Some of my memories are a bit warped because I’m an adult rememberin things that happened when I was a child. For instance, I remember walking through bookcases in the adult section of the library when I was about five years old and the bookcases towered over my head. In my memory, those bookcases must be fifteen feet tall but that’s because I’m six feet tall now and I imagine them towering over my grown-up head. In reality, they were likely about seven feet tell and I was only three feet tall. Similarly, the intervenous needle that I got when I was eight or so has grown in length because I remember the length of it by looking at my hand and my hand has grown considerably since then.

I remember some things that I’m pretty sure didn’t happen and were probably only dreams (e.g., the backyard covered with candy wrappers that my sister and a friend had thrown there when they were pigging out on candy). In some cases, I’m sure I remember what I’ve been told about things I did or said: I remember the story; I don’t remember actually doing or saying those things.

Of many other events, I remember bits and pieces: being six years old in the winter and freezing my hands as I scrambled up a snow-covered hill on my way home from school, having forgotten my mittens at school, for instance. I remember that part, and I remember my mother having me run lukewarm water over my hands. But that’s it. I don’t remember if it was sunny or overcast; I don’t remember whether we ever found those mittens again.  I have only parts of those memories left, and if I were to write a memoir about my childhood it would either be very brief, full of scattered pieces of memories, or I would have to embellish it significantly.

And now I come back to Angela’s Ashes. All the way through this memoir, I kept wondering how McCourt, who was in his sixties when he wrote the book, could possibly remember all the details he records. He reports on whole conversations that took place when he was three years old, for instance. He describes buildings and people and their accents and the way he felt and so forth. Now perhaps, as my memory of childhood may be unusually sparse, his was unusually good. Perhaps some of the stories he tells were ones that his parents told him about his chlidhood, so that he’s remembering their account rather than the actual events. Maybe.

But I kept suspecting that McCourt was embellishing the stories he told, that he wasn’t simply reporting on what he remembered or even what others told him but that he was making things up in order to make the stories more interesting. We all probably do some of that when we’re telling stories about things that happened to us, just as the fish that got away seems larger than it probably really was. Most of us are probably wittier and have better comebacks in our stories than we do in real life. And I suspect that McCourt has told these stories often in one form or another — and especially in this play — that they’ve gradually grown in the telling, especially as he found that people chuckled at the things he was saying.

In his review, Orrin Judd raises similar questions:

What then are we to make of the recent torrent of memoirs wherein authors recall entire conversations including tones and nuances, scents, sounds, shadows and so forth from when they were mere children? Obviously we just can not accept them as non-fiction. There was a time when every young writer was expected to start his career with a thinly veiled autobiographical novel, then, having gotten that out of his system, he could move on to writing genuine fiction, coming back in his dotage to retell the story of his early life in a memoir that was understood to be so far removed from the time of the events that it was inherently untrustworthy. No one took these memories seriously, but the aged author had earned the right to put his own gloss on the misty past; only petty minds demanded total accuracy from these literary lions. Now, however, everyone who picks up a pen writes a memoir of some kind or another, recreating their callow youths with such exacting specificity that it is impossible to believe a word they’ve written. The only reason for this trend would seem to be the truly frightening level of voyeurism we’ve sunk to in recent years. Like the glut of “reality” TV shows, the craze for memoirs appears to be based on the assumption that a story is more interesting if we think it’s true. One would hope that this is not necessarily the case and that in due time authors will return to writing coming of age novels which may leave us guessing what is fact and what is fiction, but have the honesty and the decency not to pretend that fiction is fact.

None of this means that Angela’s Ashes isn’t worth reading, but it would probably be better to approach it as if you were sitting in a crowd listening to a gifted storyteller spinning yarns about his youth in order to make you laugh and sometimes cry. You don’t necessarily believe everything he says, but you can still enjoy the stories.

Sons or Tools

In a chapter comparing John Milton’s theology with that of St. Augustine, C. S. Lewis points out that Milton and Augustine both shared a belief in God’s sovereignty. That’s particularly interesting because Milton himself was, if I understand things correctly, no Calvinist. Nor, for that matter, was Lewis, though he quite seems to approve the doctrine he’s describing here which is nothing short of a doctrine of God’s complete sovereignty even over evil. It’s really the last line that made me want to quote it here:

Though God has made all creatures good He foreknows that some will voluntarily make themselves bad (De Civ. Dei, XIV, II) and also foreknows the good use which He will then make of their badness (ibid.). For as He shows His benevolence in creating good Natures, He shows His justice in exploiting evil wills. (Sicut naturarum bonarum optimus creator, ita voluntatum malarum justissimus ordinator, XI, 17.)

All this is repeatedly shown at work in the poem [Paradise Lost]. God sees Satan coming to pervert man; “and shall pervert,” He observes (III, 92). He knows that Sin and Death “impute folly” to Him for allowing them so easily to enter the universe, but Sin and Death do not know that God “called and drew them thither, His hell-hounds to lick up the draff and filth” (X, 620 et seq.). Sin, in pitiable ignorance, had mistaken this Divine “calling” for “sympathie or som connatural force” between herself and Satan (X, 246).

The same doctrine is enforced in Book I when Satan lifts his head from the burning lake by “high permission of all-ruling Heaven” (I, 212). As the angels point out, whoever tries to rebel against God produces the result opposite to his intention (VII, 613). At the end of the poem Adam is astonished at the power “that all this good of evil shall produce” (XII, 470). This is the exact reverse of the programme Satan had envisaged in Book I, when he hoped, if God attempted any good through him, to “pervert that end” (164); instead he is allowed to do all the evil he wants and finds that he has produced good. Those who will not be God’s sons become His tools (A Preface to Paradise Lost 67-68, with added paragraph breaks).

Psalms or Greek Poetry?

In his preface to The Reason of Church Government, Book II, John Milton talks about the choice that confronted him when he set out to write a great poem and that led eventually to the writing of Paradise Lost. The basic choice was whether to write an epic, a tragedy or drama, or lyric poetry. In each of these categories, Milton mentions a Greek or Latin example and then a biblical example. Interestingly, following David Paraeus, Milton includes the Song of Songs and Revelation as examples of biblical drama.

As for the third category, lyric poetry, which includes the Greek poets Pindar and Callimachus, as well as the Psalms and passages in the Prophets, Milton adds something interesting. Here’s C. S. Lewis’s summary:

Almost as if he had foreseen an age in which “Puritanism” shouild be the bear seen in every bush, he has given his opinion that Hebrew lyrics are better than Greek “not in their divine argument alone, but in the very critical art of composition.” That is, he has told us that his preference for the Hebrew is not only moral and religious, but aesthetic also. I once had a pupil, innocent alike of the Greek and of the Hebrew tongue, who did not think himself thereby disqualified from pronouncing this judgement a proof of Milton’s bad taste; the rest of us, whose Greek is amateurish and who have no Hebrew, must leave Milton to discuss the question with his peers. But if any man will read aloud on alternate mornings for a single month a page of Pindar and a page of the Psalms in any translation he chooses, I think I can guess which he will first grow tired of (A Preface to Paradise Lost, pp. 4-5).

Love and Money

Last week, I read (for the first time as an adult) Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. In the introduction, which I read last, of course, Vivien Jones writes:

[T]o point out basic structural similarities between Austen’s novel and a Mills and Boon or Harlequin romance is not to reduce Austen’s achievement. Rather, it helps account for the continuing popularity of Austen’s fiction and of Pride and Prejudice in particular. The romantic fantasy which so effectively shapes Austen’s early-nineteenth-century novel is still a powerful cultural myth for readers in the late twentieth century. We still respond with pleasure to the rags-to-riches love story, to the happy ending which combines sexual and emotional attraction with ten thousand a year and the prospect of becoming mistress of Pemberly, a resolution which makes romantic love both the guarantee and the excuse for economic and social success (p. viii).

It strikes me that some readers today might think that such a combination — marriage and wealth and advancement to high social standing — reduces romance to something a bit too mercenary. Besides, such a combination is generally out of our reach. Few girls marry wealthy men and become the mistress of Pemberly, and in our day, at least here in North America, many people have developed a sort of contempt for anything or anyone high class. And yet, says Vivien Jones, the myth remains.

Why? I submit it’s because the combination of romance and love with money and high status is part of the gospel. The gospel is itself a love story, the story of the Son who sought a Bride and wooed her in spite of everything and in the end has won her. It’s a love story that ends, as happy fairy tales do, with a wedding and the couple living “happily ever after.” And it is precisely a rags-to-riches love story, for the Son who was rich becomes poor for the sake of the Bride, so that she may share in His riches and be the mistress in His house.

Penny Dreadfuls?

In his recent article on the last Harry Potter book (which, I warn you in advance, contains many spoilers), Alan Jacobs compares the Harry Potter books to the old penny dreadfuls.

A little more than a hundred years ago, a number of British educators, journalists, and intellectuals grew exercised about the reading habits of the nation’s children. The particular target of their disapproval was the boy’s adventure story—the kind of cheap short novel, full of exotic locations and narrow escapes from mortal peril and false friends and unexpected acts of heroism, that had come to be known as the “penny dreadful.” Surely it could not be good for children to immerse themselves in these ill-made fictional worlds, with their formulaic plots and purple prose; surely we should insist that they learn to savor finer fare.

G. K. Chesterton, however, wrote “A Defense of Penny Dreadfuls,” pointing out that the things these books contained are also found in great literature and arguing that the “penny dreadfuls” are actually more ethically sound than a lot of the things that more sophisticated people read:

The vast mass of humanity, with their vast mass of idle books and idle words, have never doubted and never will doubt that courage is splendid, that fidelity is noble, that distressed ladies should be rescued, and vanquished enemies spared … . The average man or boy writes daily in these great gaudy diaries of his soul, which we call Penny Dreadfuls, a plainer and better gospel than any of those iridescent ethical paradoxes that the fashionable change as often as their bonnets.

In his review, Jacobs goes on to speak of the Harry Potter books as penny dreadfuls. After all, as he says, “It is a story full of exotic locations and narrow escapes from mortal peril and false friends and unexpected acts of heroism; it is a story which suggests that courage is splendid and fidelity noble.” And near his conclusion, he writes:

It should be obvious at this point that the Harry Potter books amount to something more, far more, than your average penny dreadful. But they belong, firmly, to that moral universe, even as they expand it beyond what we might have thought possible. Many years ago Umberto Eco wrote that the greatness of Casablanca stems from its shameless deployment of every narrative cliché known to humankind: “Two clichés make us laugh. A hundred clichés move us. For we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, and celebrating a reunion.” The Harry Potter books are like that: every trope and trick of the penny dreadful raised to the highest power and revealed in all their glory.

I love that Umberto Eco quotation, and I appreciate what Jacobs is saying. He is certainly a perceptive reader of Rowling’s novels.

And yet I do wonder if it’s really fair to put Harry Potter in the category of “penny dreadfuls.” The Hardy Boys books could easily fit in that category, although they’re probably tamer than some of the books Chesterton was speaking of and Frank and Joe themselves were perhaps more restrained that some of Chesterton’s heroes. But these books are full of adventures to be faced with pluck and courage. And yet there’s virtually no maturation taking place in the entire series. Each book presents a set of adventures, a set of challenges, a mystery to be figured out. But that’s it.

On an adult level, virtually any novel by Agatha Christie could be seen as a sort of grown-up “penny dreadful.” Hercule Poirot does not change. He doesn’t mature and grow. Nor does Hastings. Nor does Mrs. Marple. They’re always the same and only the mysteries they solve change. For that matter, all the novels of P. G. Wodehouse, which are almost the same novel anyway, while certainly not “dreadful” in any sense, are similar to the penny dreadfuls in that they simply present a series of (highly enjoyable) incidents.

But Harry Potter is far different. Yes, the Harry Potter books can be classified as “genre fiction.” They are fantasy novels. They are also school stories, which is a genre unique to Britain where public schools are boarding schools. But a novel which is genre fiction is not necessarily the same thing as a penny dreadful. The Lord of the Rings is a fantasy novel, but it’s a far cry from the Hardy Boys or the adventures of Dick Deadshot.

And the Harry Potter novels, it seems to me, are far closer to The Lord of the Rings than they are to any of the penny dreadfuls of the past or present.Â

One way of getting at the difference, it seems to me, is through something C. S. Lewis says in A Preface to Paradise Lost when he compares Homer and Virgil. Virgil has a much bigger sense of time than Homer does, Lewis says. More than that, he is interested in the turning points in history, the points of transition. Homer and the Greeks were focused more on the timeless; Virgil is interested in the changes that make history. Lewis writes about the Aeneid,

In a sense he [Aeneas] is a ghost of Troy until he becomes the father of Rome. All through the poem we are turning that corner. It is this which gives the reader of the Aeneid the sense of having lived through so much. No man who has once read it with full perception remains an adolescent (p. 37).

Furthermore, Virgil, unlike Homer, is concerned with vocation, the kind of calling that is both duty and desire and that drives me to leave behind things they might otherwise love: “To follow the vocation does not mean happiness: but once it has been heard, there is no happiness for those who do not follow” (p. 39).

Virgil thus took a great step forward:

I have read that his Aeneas, so guided by dreams and omens, is hardly the shadow of a man beside Homer’s Achilles. But a man, an adult, is precisely what he is: Achilles had been little more than a passionate boy. You may, of course, prefer the poetry of spontaneous passion to the poetry of passion at war with vocation, and finally reconciled. Every man to his taste. But we must not blame the second for not being the first . With Virgil European poetry grows up. For there are certain moods in which all that had gone before seems, as it were, boys’ poetry, depending both for its charm and for its limitations on a certain naivety, seen alike in its heady ecstasies and in its heady despairs, which we certainly cannot, perhaps should not, recover. Mens immota manet, “the mind remains unshaken while the vain tears fall.” That is the Virgilian note. But in Homer there was nothing, in the long run, to be unshaken about. You were unhappy, or you were happy, and that was all.  Aeneas lives in a different world; he is compelled to see something more important than happiness  (pp. 37-38).

Perhaps the application to the penny dreadfuls and Harry Potter is already clear. The penny dreadfuls are Homerian, if you will. They simply tell of adventures and derring-do. They are boys’ literature. But Harry Potter, like The Lord of the Rings, is much more Virgilian, even though it deals with a boy. It deals with him as someone growing up to become a man, someone bound by a vocation which is both duty and desire and which is more important than mere happiness.

But let me go a step beyond Lewis: Greater far than Virgil is the story of Christ, the epic which is Scripture. I was struck as I read Lewis’s chapter by some of the similarities Lewis traces between Virgil’s approach and some Scriptural themes, which was part of Lewis’s point.

And yet it strikes me, too, how much more mature the story of Scripture is than even the story Virgil tells, for it is not simply the story of the great hero who follows his vocation in spite of tears, grows to maturity, and then attains a glorious triumph and the establishment of an eternal city. It is the story of the great hero who suffers and dies en route to that victory, whose suffering and death is that victory, the great hero whose true heroism consists in his laying down his life for his friends. Virgil doesn’t yet know that sort of self-sacrifice and to Homer’s heroes it would be reprehensible, the mind of a slave, as it was even to the Roman culture at the time of Christ.

And that is the story that Harry Potter is closest to: certainly not Homer or the penny dreadfuls with their brave heroes and derring-do and one set of adventures after another, not even Virgil with his teary-eyed hero stoically aiming at his destiny, but the story of Christ. Unlike the penny dreadfuls, these novels are one consistent whole and that whole is a story of maturation and Christ-like self-sacrifice.

Lewis on Williams

Although C. S. Lewis delivered the lectures which became A Preface to Paradise Lost at the College at Bangor, he chose not to dedicate the book to the college. Instead, he dedicated it to Charles Williams, in part because his own lectures reminded him of Williams’ lectures at Oxford, lectures on John Milton’s poem “Comus,” but lectures which did more than just impart some knowledge about Milton or the poem because they also focused on the virtue Milton was praising:

The scene was, in a way, medieval, and may prove to have been historic. You were a vagus thrown among us by the chance of war. The appropriate beauties of the Divinity School provided your background. There we elders heard (among other things) what we had long despaired of hearing — a lecture on Comus which placed its importance where the poet placed it — and watched “the yonge fresshe folkes, he or she,” who filled the benches listening first with incredulity, then with toleration, and finally with delight, to something so strange and new in their experience as the praise of chastity.

Reviewers, who have not had time to re-read Milton, have failed for the most part to digest your criticism of him; but it is a reasonable hope that of those who heard you in Oxford many will understand henceforward that when the old poets made some virtue their theme they were not teaching but adoring, and that what we take for the didactic is often the enchanted. — C. S. Lewis, “Dedication: To Charles Williams,” A Preface to Paradise Lost, p. v.

I love this description of Williams’ lectures. Williams didn’t have a degree, but Lewis had managed to get him a chance to lecture at Oxford. Lewis describes the second lecture briefly in the quotation above, but he described it in more detail to his brother in a letter:

On Monday, C. W. lectured nominally on Comus but really on Chastity. Simply as criticism it was superb — because here was a man who really started from the same point of view as Milton and really cared with every fibre of his being about “the sage and serious doctrine of virginity” which it would never occur to the ordinary modern critic to take seriously. But it was more important still as a sermon. It was a beautiful sight to see a whole room full of modern young men and women sitting in that absolute silence which can not be faked, very puzzled, but spell-bound: perhaps with something of the same feeling which a lecture on unchastity might have evoked in their grandparents — the forbidden subject broached at last. He forced them to lap it up and I think many, by the end, liked the taste more than they expected to. It was “borne in upon me” that that beautiful carved room had probably not witnessed anything so important since some of the great medieval or Reformation lectures. I have at last, if only for once, seen a university doing what it was founded to do: teaching wisdom. And what a wonderful power there is in the direct appeal which disregards the temporary climate of opinion — I wonder is it the case that the man who has the audacity to get up in any corrupt society and squarely preach justice or valour or the like always wins? — C. S. Lewis to Warnie Lewis, 11 February 1940, in Letters of C. S. Lewis, pp. 339-339.

The Two Faces of Tobacco

This morning, I finished reading Patrick O’Brian’s The Mauritius Command, the fourth in his series of novels about Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin. As usual, it was absolutely delightful. In this one, Aubrey is a commodore in the Indian Ocean, still during the time of the Napoleonic wars, with Maturin along as ship’s doctor and a bit more.

Here are Stephen’s comments about how well one of his prescriptions was working for a colleague’s patient:

“May we not in part attribute his activity to the roborative, stimulating use of coffee, and to the general soothing effect of mild tobacco, which has set his humours in equilibrio? Tobacco, divine, rare, superexcellent tobacco, which goes far beyond all their panaceas, potable gold, and philosopher’s stones, a sovereign remedy to all diseases. A good vomit, I confess, a virtuous herb, if it be well qualified and opportunely taken, and medicinally used, but as it is commonly abused by most men, which take it as tinkers do ale, ’tis a plague, a mischief, a violent purger of goods, lands, health; hellish, devilish and damned tobacco, the ruin and overthrow of body and soul. Here, however, it is medicinally taken; and I congratulate myself upon the fact that in your hands there is no question of tinkers’ abuse” (pp. 201-202).

So there you have it: the next time you’re feeling down and sick, Dr. Maturin prescribes coffee and a mild cigar, taken opportunely.

Family Camp

Last week, Moriah and I attended Reformation Covenant Church‘s annual family camp on the Oregon coast near Rockaway Beach. We arrived Sunday evening and returned home again Saturday.

The speaker this year was Peter Leithart, who gave a series of lectures on prayer. In the first, he told us that he had only two things to say all week: (1) Pray, and (2) Pray according to the Scriptures. But of course that last exhortation was the one that we often need unpacked more, which he proceeded to do, showing us some things in the Scriptures that ought not only to encourage us to pray but also to shape our prayers.

For instance, he spent part of one lecture dealing with whether we are righteous. James says that the effective fervent prayer of a righteous man avails much, but, some say, we aren’t righteous. We’re miserable sinners. Leithart strongly emphasized that in Christ we are righteous and, more than that, that God is changing us to be faithful and righteous. This promise in James isn’t only for specially holy people; it’s meant to comfort all of us and move us to pray fervently.

A couple of the lectures dealt with the imprecatory prayers in Scripture and with the authority of believers and of the church to pass the sorts of judgments contained in the imprecatory psalms. Other lectures covered such matters as unanswered prayers and the relationship between personal prayer and corporate liturgical prayer. The lectures are available from Reformation Covenant Church.

I very much like the camp’s schedule. There was a lecture in chapel in the morning and one in the evening, both begun with some very enthusiastic and beautiful singing led by Mark Reagan from Moscow, Idaho, who taught us several songs, some of which he himself composed. But the rest of the day was basically free. There were games and competitions. Some people went to the beach. Some sat and read. Almost every evening there was a campfire, one evening there was a ball, and the final evening was the talent night. I’d highly recommend this camp to you.

We greatly enjoyed spending time with some old friends and meeting some new ones.

During the camp, I finished up Gene Wolfe’s magnificent The Wizard, which is the second volume of his two-volume novel The Wizard Knight. The ending, as if often the case with Wolfe’s books, made me want to start reading the novel from the beginning all over again, looking for clues I’d missed and trying to figure out some of the stuff that I didn’t catch the first time.

I also read a good chunk of Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran, which I highly recommend, not only for the main story, which is about a literature prof in Iran during the Islamic revolution, but also for its discussion of several novels, including Lolita, The Great Gatsby, and Pride and Prejudice. She made me want to read the books she was discussing. I especially appreciated her approach to Pride and Prejudice, treating it as a sort of dance, where the characters draw together and then apart in various combinations.

I also started read Brendan O’Donnell’s Rain from a Rainless Sky: A Work of Theological Botany. Brendan is a friend of mine and this book was his dissertation at New St. Andrews College.

I had heard some time ago that Brendan was doing his dissertation on sagebrush, and sagebrush is indeed what this book is about. But it’s also about the symbolism of the world God has created and why God, who spoke the world into existence, has created “words” like sagebrush and places such as the desert of western Washington. It’s about apostasy, and how thorns and thistles can grow in the church and choke out life. It’s about the history of Israel and the coming of Jesus. It’s about Gene Robinson, the homosexual bishop of New Hampshire, and about Peter Akinola, the bishop of Nigeria.Â

Brendan writes well. He makes you smell and feel and perhaps even taste the sagebrush, nor does he rush to give you answers or the finished results of his meditations on why there is such a thing as sagebrush. He makes you share his quest and his questions. Would that there were more such books.

And now that I’m home, by the way, I’m reading N. D. Wilson’s Leepike Ridge, which is a very fun young adults adventure story. C’mon: Buy a copy and let’s cataput Nate into teenage stardom (albeit a bit late).

Slow Reading

Recently, on a couple of my friends’ blogs, I’ve seen mention of this article about doubling the speed with which you read. [HT: Alastair and Pete.] There’s some stuff in that article which would probably be helpful for a lot of readers (e.g., finding your motivation and eliminating distractions).

Still, I wonder a bit about the value of speed reading. True, there are certain things that are worth only a quick read. There’s no point in slowly, painstakingly working your way through a lot of novels. And if you’re just reading for information, then it’s fine to skim or speed-read, looking for answers to your questions: “When was this town founded? What was its population then?” and so forth.

But not everything ought to be read at breakneck speed, and though (as this article points out) subvocalizing is the number one thing that slows down your reading, there are times when subvocalization is best, as the follow-up article says:

Subvocalization can be useful. Just like it isn’t always wise to read fast, sometimes it makes sense to subvocalize. My article focused on how to read faster, but sometimes you need to read slower. Better reading comes from having a brake and a gas pedal not just one or the other. If you are having trouble comprehending, slowing down so you start subvocalizing again can eliminate distractions and refocus your mind on the material.

I have to admit that I’m a notorious and unrepentant subvocalizer. I can read some things quickly and I don’t subvocalize all the time, but a lot of the time I’m saying the words in my mind as I read them.

I blame it on Walter Wangerin. Years ago, when I was just a teenager who wanted to be a writer, I read an interview with him, probably in Christianity Today. I can’t recall whether Wangerin said he subvocalizes when he read because he loves the sound of words and the way a good author puts them together or if he said it was the fact that he subvocalized as a kid that contributed to his love of words and good writing. One or the other: it doesn’t matter. I may have subvocalized before reading that article, but I did it deliberately after because I wanted to write and to write well and so I wanted to hear how good writing sounds to the ear.

I’m unrepentant, I say. I still love the sound of words and words together.

If I were to speed-read Dubliners I could get the gist of what James Joyce is saying, but I wouldn’t hear the stories and in particular I wouldn’t hear the voice of the narrator or the various characters speaking. Joyce used to write down conversations he overheard, I’m told, so that he could learn how to write dialogue the way it actually sounds. It must have worked: I was in Bible college with an Irish girl and I hear traces of her voice in everything Joyce writes.

I can’t imagine wanting to speed-read Joyce. Or Larry Woiwode, whose writing is always bordering on poetic and whose descriptions are so real it’s hard to believe that he hasn’t actually lived through exactly what he’s talking about himself. Or P. G. Wodehouse or Raymond Chandler or Ross MacDonald, all of whom use striking metaphors you don’t want to speed past.

Or Gene Wolfe, whose writing in many of his books is fairly easy to read and might fool you into thinking you can pick up the pace, but who is hiding clues in plain view. You could read through The Book of the Long Sun in a couple days if you wanted, especially if you’re reading 900 words a minute the way the writer of this article can. But you would miss the symbolism and all the puzzles Wolfe loves to include, and all you would get is a bare sense of the basic plot but little of what makes Wolfe worth reading.

And can you imagine skimming a poem? Yes, you could do it. You could catch the basic gist (“This one’s about how his love is like a red rose and this other one is about growing old”) but you’d miss the poem itself. Poetry depends on you listening to the words and even sounding them out.

It’s like food. You can wolf down a Big Mac and be out of the restaurant in a matter of minutes. But should you try to do that with your filet mignon and your glass of pinot noir in a classy restaurant? Or with the meal your wife made for dinner? No. Fast food has its place, but slow food is better. It’s better to take your time with a meal, to savor it, to visit with your family and friends and guests over the meal, to linger.

It’s okay to skim something quickly. It’s okay to speed-read some books. It’s sometime wise to skim a book first, get the gist of the argument and where the book’s heading, and then go back and read it more carefully. And sometimes you have only so much time and so all you can do is read as much as you can as quickly as you can.

But if you’re reading Scripture, read it slowly. In fact, the command in Scripture is not to read the Bible; it’s to hear it. And if you’re reading something beautiful, if you’re reading for the pleasure of words and the way they’re put together and to savor the writing or pick up the author’s clues or follow his arguments, slow down. Sound out the words in your head and enjoy them.

Speed reading? It has its place. But let’s hear it for the slow reading movement.

Pirate Freedom

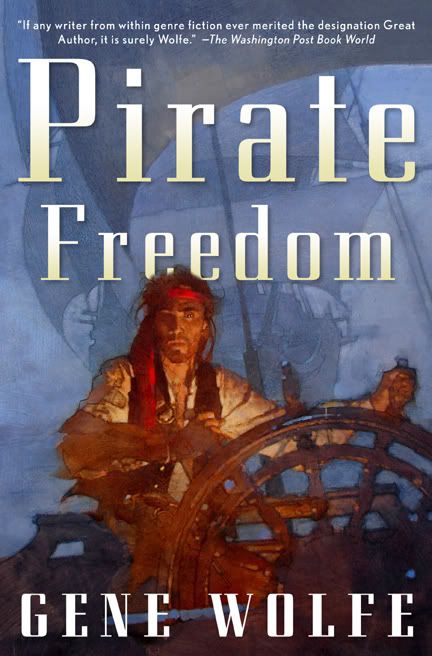

Something to look forward to…. The latest novel from Gene Wolfe, coming out this fall. [HT: Irene Gallo.]

Â