Category Archive: Art

Mrs. Burne-Jones

Angela Thirkell talks about how her grandmother — the wife and, later, widow of the painter, Edward Burne-Jones — used to have workingmen into her home to read to them about Pre-Raphaelitism and socialism: “All the snobbishness latent in children came to the fore as we watched the honoured but unhappy workman sitting stiffly on the edge of his chair in his horrible best clothes while my grandmother’s lovely earnest voice preached William Morris to him.”

In spite of her wide affections and deep understanding she was curiously removed from real life and I think she honestly believed that The Seven Lamps of Architecture on every working-man’s table would go far to ameliorate the world. She was absolutely fearless, morally and physically. During the South African War her sympathies were with the Boers, and though she was at that time a widow, living alone, she never hesitated to bear witness, without a single sympathizer. When peace was declared she hung out of her window a large blue cloth on which she had been stitching the words: ‘We have killed and also taken possession.’ For some time there was considerable personal danger to her from a populace in Mafeking mood, till her nephew, Rudyard Kipling, coming over from The Elms, pacified the people and sent them away. Single-minded people can be a little alarming to live with and we children had a nervous feeling that we never knew where our grandmother might break out next. — Angela Thirkell, Three Houses, pp. 78-79, 79-80.

Pre-Raphaelite “Comfort”

What would it be like to live in a house with furniture designed by, say, William Morris or someone with similar ideals? Lest anyone read John Ruskin or Morris or the various Pre-Raphaelites and think he’d like to live in such an abode, I offer this from Angela Thirkell, the granddaughter of Edward Burne-Jones:

Curtains and chintzes in The Bower were all of Morris stuffs, a bright pattern of yellow birds and red roses. The low sofa and the oak table were designed by one or other pre-Raphaelite friend of the house, or made to my grandfather’s orders by the village carpenter.

As I look back on the furniture of my grandparents’ two houses I marvel chiefly at the entire lack of comfort which the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood succeeded in creating for itself. It was not, I think, so much that they actively despised comfort, as that the word conveyed absolutely nothing to them whatever.

I can truthfully say that neither at North End Road nor at North End House was there a single chair that invited to repose, and the only piece of comfortable furniture that my grandparents ever possessed was their drawing-room sofa in London, a perfectly ordinary large sofa with good springs, only disguised by Morris chintzes.

The sofas at Rottingdean were simply long low tables with a little balustrade round two, or sometimes three sides, made of plain oak or some inferior wood painted white. There was a slight concession to human frailty in the addition of rigidly hard squabs covered with chintz or blue linen and when to these my grandmother had added a small bolster apparently made of concrete and two or three thin unyielding cushions, she almost blamed herself for wallowing in undeserved luxury….

As for pre-Raphaelite beds, it can only have been the physical vigour and perfect health of their original designers that made them believe their work was fit to sleep in. It is true that the spring mattress was then in an embryonic stage and there were no spiral springs to prevent a bed from taking the shape of a drinking-trough after a few weeks’ use, but even this does not excuse the use of wooden slats running lengthways as an aid to refreshing slumber.

Luckily children never know when they are uncomfortable and the pre-Raphaelites had in many essentials the childlike mind. — Angela Thirkell, Three Houses, pp. 64-65.

Heredity … of a Sort

Angela Thirkell was the granddaughter of the painter Edward Burne-Jones, who was influenced in his early years by Gabriel Rossetti but who later developed his own style and his own ideals of beauty, which he transmitted not only in his art but, surprisingly, also in his progeny. She talks about the “pure ‘Burne-Jones’ type” of woman:

The curious thing is — and it ought to open a fresh field of inquiry into heredity — that the type which my grandfather evolved for himself was transmitted to some of his descendants.

In his earlier pictures there is a reflection of my grandmother in large-eyed women of normal, or almost low stature, as against the excessively long-limbed women of his later style. But the hair of these early women is not hers, it is the hair of Rossetti’s women, the masses of thick wavy hair which we knew in “Aunt Janey,” the beautiful Mrs. William Morris. When I remember her, Aunt Janey’s hair was nearly white, but there were still the same masses of it, waving from head to tip.

To any one who knew her, Rossetti’s pictures — with the exception of his later exaggerated types — were absolutely true. The large deep-set eyes, the full lips, the curved throat, the overshadowing hair, were all there. Even in her old age she looked like a queen as she moved about the house in long white draperies, her hands in a white muff, crowned by her glorious hair.

But when my grandfather began to develop in a different direction from his master Gabriel he saw in his mind a type of woman who was to him the ultimate expression of beauty. Whenever he saw a woman who approached his vision he used her, whether model or friend. Some of my grandparents’ lasting friendships were begun in chance encounters with a “Burne-Jones face” which my grandfather had to find a way of knowing.

As my mother grew up she was the offspring of her father’s vision and the imprint of this vision has lasted to a later generation. I do not know of another case in which the artist’s ideal has taken such visible shape as in my mother.

If the inheritance were more common one would have to be far more careful in choosing one’s artist forbears. El Greco, for instance, or Rowlandson, would be responsible for such disastrous progeny from the point of view of looks. — Angela Thirkell, Three Houses, pp. 23-24.

Moral: Be careful what and whom you admire. If Thirkell is right, your children might just look like that.

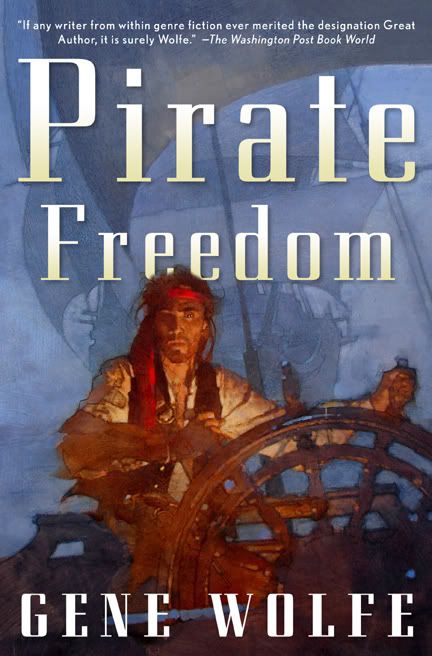

Pirate Freedom

Something to look forward to…. The latest novel from Gene Wolfe, coming out this fall. [HT: Irene Gallo.]

Â

Creativity

… as I age I become ever more alert to the creativity of those who do not produce a commodity, a product, a tangible document of their urge — a play, an essay, a film, a song, a painting, a dance, a meal, a house, a carving, a tapestry. Mothers shape love and macaroni and sleeplessness and soap into young men and women over the course of many years; is there a greater art, or a more powerful patient creativity than that? — Brian Doyle, Leaping: Revelations and Epiphanies, p. xxi.

Imagine

Last week, I read Steve Turner’s Imagine: A Vision for Christians in the Arts. I’d spotted it in the Medford Public Library and thought it looked interesting. And it was.

Turner is a poet and music journalist and has written several books and articles about musicians, so he knows what he’s talking about.  He does a very good job at pointing out the ways in which the arts contribute to a full life.  Dance, for instance, makes us aware of the beauty and grace of the human body.

Whereas some books on the arts focus solely on artists who are themselves creating new pieces of art, Turner recognizes that not every artist does. Musicians in a symphony simply play the notes that are in front of them. Similarly, there are actors who simply have to say the lines that have been written for them.  It strikes me that Turner is unique in addressing what it means for such artists to carry out their art in a Christian way.

Turner distinguishes helpfully between what he presents as “five concentric circles” of artistic work. In the outermost circle are the sorts of artists I mentioned above, and Turner affirms that there’s nothing wrong with simply playing the notes or acting a role. The creation of something beautiful is valuable, even if no one hearing the musician play those notes would be able to tell that he is a Christian.

The next circle is the kind of artistic work that does express “Christian faith because it dignifies human life and introduces a sense of awe” (p. 83).  Think of a saxophone solo that makes you glad to be alive or a photograph that shows you a beautiful scene or a poem that sheds new light on some aspect of ordinary life.

The third circle is the kind of artistic work that expresses the Bible’s teaching but in a way that is not specificially Christian. Unbelievers, too, can often affirm the importance of forgiveness or appreciate humble care for the poor. The fourth circle is more explicitly Christian, drawing on biblical and theological themes such as original sin. The fifth and central circle is the most explicitly Christian, presenting the cross and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Turner notes rightly that all of these circles are legitimate artistic endeavours for Christians. He traces the history of Christian appreciation and avoidance of the arts. It’s sad to see that, whereas the Roman Catholic church often embraced and supported her artists, the Protestant world often didn’t.  Turner interacts (often sympathetically) with some of the Protestant cautions with regard to the arts.

At various points in the book, he speaks about the superficiality of much of the art that Christians produce. Christians shouldn’t focus their artistic endeavors simply on the gospel as if they were simply interested in propaganda. It’s not wrong to produce music about ordinary life; Christians as much as unbelievers enjoy drinking good coffee or falling into bed at the end of a hard day or loving their wives or walking under the stars and they shouldn’t feel as if singing about these things is less godly or less “spiritual” than singing about Jesus.

Furthermore, they shouldn’t shy away from talking honestly about sin.

Adultery, violence, murder, deceit, fornication, betrayal and pride are clearly important to adult storytelling, whether in fiction, in film or on the stage. A simplistic reading of the situation would conclude that these sins are included to appeal to the base in human nature. Sometimes they are. But it is often more deep rooted than that. Drama depends on conflict. The protagonist must face tests and trials and through overcoming them, reveal his or her true character. Violence and sexual betrayal are among the most extreme tests we can face, which is why they are so frequently used in story lines (p. 39).

After pointing to the stories of David and Saul and David and Bathsheba, Turner continues:

If the obstacles the writer introduces either don’t seem challenging enough (for example, the protagonist is handed back too much change in a store and worries about whether to return it) or doesn’t seem real enough (for example, a fight ensues but no punches are seen to land and no blood is spilled), then evil doesn’t appear evil enough, and if good triumphs, it won’t appear good enough. This is why so much “Christian fiction” lacks the ring of truth. The action doesn’t appear to take place in the “real world” (pp. 39-40).

Turner follows up with some quotations:

Mindful of his Calvinistic heritage Daniel Defoe argued in the preface to Moll Flanders: “To give the history of a wicked life repented of, necessarily requires that the wicked part should be made as wicked as the real history of it will bear, to illustrate and give beauty to the penitent part, which is certainly the best and brightest, if related with equal spirit and life.” Francois Mauriac said that his job as a novelist was to make evil “perceptible, tangible, odorous. The theologian gives us an abstract idea of the sinner. I give him flesh and blood.” Or, as John Henry Cardinal Newman once observed, “It is a contradition in terms to attempt a sinless literature of sinful man” (p. 40).

Instead, too many Christians shy away from realistic portrayals of sin, presenting a Pollyanna view of life, “paintings of birds and kittens, movies that extol family life and end happily, songs that are positive and uplifting — in short, works of art that show a world that is almost unfallen where no one experiences conflict and where sin is naughty rather than wicked” (pp. 40-41).

But presenting the truth about sin doesn’t mean that the artist has permission to be worldly. Turner warns that we are perhaps most in danger of succumbing to worldly ideas when we’re just watching something for fun, but he is careful to identify what worldliness is and isn’t. It’s the rebellious system of thinking and acting that characterizes unbelieving people; it isn’t a disdain for the world around us.

Confusing these two usages can lead to disaster. Some strict fundamentalist sects show disdain toward creation and culture, and yet in doing so become proud, arrogant and uncaring. They therefore become worldly in the very way the Bible condemns and yet are not worldly enough in the way the Bible commands. We are told to be in the world but not of it. People like this are often of the world but not in it (p. 43).

This sort of “unworldiness” which emphasizes the “spiritual” and rejects “the secular” (that is, anything that isn’t directly about Jesus) — a view which Turner correctly identifies as having its roots in the heresy of gnosticism — can damage people and drive them away from Jesus:

When I was researching my book Trouble Man: The Life and Death of Marvin Gaye I visited an African American church in Kentucky where one of the pastors asked me this question: “Gospel music is made for the glory of God, but for whose glory is pop music made?”

I assumed I was meant to think that if someone wasn’t singing about God, they couldn’t be singing to God’s glory and that if they weren’t singing for God’s glory then they must be singing to the glory of the devil. It’s a tortured logic but one I have seen affect some of the most innovative artists in rock music. It can lead people to think that they are damned for singing a song about the joy of being in love or driving a fast car (p. 46).

And so people like Sam Cooke and Jerry Lee Lewis, but doubtless many others, found themselves confronted with a choice: sing gospel music only or leave the church to sing “secular music.” And if you’re going to be treated as a rebel, then you may as well act like one. And so they have, working out the gnosticism their churches taught them.

And yet those aren’t the only choices. The church needs to embrace and appreciate its artists, even though artists often don’t fit in well. And artists need the church, too.

Toward the end of the book, Turner calls Christian artists to be faithful church members instead of edgy outsiders. Turner cites the poet Jack Clemo who left the Calvinistic Methodist church he grew up in but returned to the church later in life:

At first I steered clear of the church, having a sort of “poetry religion,” but a Christian can’t develop much on poetry religion. We all need the religion of ordinary people and the love of other converts. That’s why, in the end, I went back to church; to worship around people who don’t like poetry. It’s a good discipline. I can’t put myself apart from them as someone very special. As a convert I am just an ordinary believer, worshipping the same Lord as they do (p. 122).

Turner adds:

The church humbles us. It is one of the few places in our societies today where we sit with rich and poor, young and old, black and white, educated and uneducated, and are focused on the same object. It is one of the few places where we share the problems and hopes of our lives with people we may not know. It is one of the few places where we sing as a crowd. Although the church needs its outsiders to prevent it from drifting into dull conformity, the outsiders need the church to stop them from drifting into individualized religion (p. 122).

There’s a lot more packed into these 131 pages: including a good discussion of how poets and musicians write (they don’t first have an idea and then start writing; they often just come up with words or phrases that get stuck in their head or sound good with the music, even if they don’t make much sense by themselves), the politics of “Christian worldview” (why is it that some Christians would identify a song against abortion as demonstrating a “Christian worldview” while a song about third-world debt wouldn’t qualify?) and a helpful chapter about U2. Buy a copy for an artist friend. And then read it yourself too.

The Minor Themes

Here’s a snippet from James Jordan’s “Biblical Perspectives on the Arts” (Biblical Educator 4.1). It was written in 1982 and I don’t know if Jim would put it the same way today, but I thought it was worth passing on:

Francis Schaeffer, in his fine booklet Art and the Bible (Intervarsity), mentions what he calls the major and the minor themes in Christian art. The minor themes are sin, depravity, ugliness, and the like. The major themes are salvation, righteousness, beauty, and the like. Because Christian fine arts are realistic, they deal with the minor themes, but they show the triumph of the major themes. This need not be true in each and every piece of art, but will be the message of the corpus of an artist’s work as a whole….Because fine arts often deal with the minor themes as well as the major ones, fine arts are not always “beautiful.” To bring across the horror of sin, the fine arts sometimes present what we might call “anti-beauty,” but the overall tendency is to create a fuller beauty as the ultimate goal.

Tolkein has put it very well in the opening passages of the Silmarillion. Satan abstracts one small set of notes from the great hymn of the angels, and harps only on them; but God is able to turn this dissonance into a new tragic melody, which eventually works its way back into the hymn, and the last beauty is greater than the first.