Theologies of Kissing

I came across this the other day: a list of various theologians and their theologies of kissing. The authors have done a great job of capturing the style and tone of the various theologians. Scroll through the comments and you’ll find more.

Now these “theologies” are, of course, all made up by the various writers. I suspect, though, that Augustine (whose theology, as Peter Leithart has said, is as large as life and sometimes larger) might have had an actual theology of kissing.

And why not? The Bible actually talks a fair bit about kissing. Think of “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth” in the Song of Songs, and Paul’s frequent encouragement to greet one another with a holy kiss. So it would certainly be possible to write a theology of kissing.

It might go something like this: Eating, in the Bible, has to do with communion. That’s why sacrifices in the Bible are called “food for God”: God “eats” them and in so doing “eats” the worshipers who presented them, drawing them into His fiery presence. Similarly, when we eat the Lord’s supper, we have communion with Christ and with each other.

We eat with our mouths and with our mouths we kiss. The kiss is a symbolic eating. “I could eat you up!” lovers sometimes say, and parents say that to their babies as they pretend to gobble up their tummies. And because it’s a symbolic eating, it’s also a form of close communion.

That’s not all that could be said, but now the ball is in your court. What is the biblical theology of kissing?

Who Keeps Time?

In his very enjoyable A Dresser of Sycamore Trees: The Finding of a Ministry (the title is taken from Amos 7:14-15), Garret Keizer describes his work as the clock-winder of the church clock in the town in Vermont where he serves as the lay pastor of Christ Church (Episcopal). Just as you start spotting Hondas as soon as you buy a Honda yourself, Keizer has become aware of mechanical clocks all over the place.

He points out something worth considering:

I also realized that the public keeping of time has passed from the church and possibly the municipal building to the branch bank. In most towns of any size, that is the place to look for a digital display of the right time. The location of the public clock has something to say, I think, about the way a culture gives meaning to time. It was logical for a church to tell people the time when one of the things they needed to know time for was when to pray, and when church feasts and holy days colored the calendar. Equally logical is it that the bank should tell the hours to a populace for whom time is not liturgical but financial, who inhabit a fiscal year broken into quarters and the maturation periods of certificates of deposit (p. 86).

Psalm 14

A reminder: I’ve prepared these psalms for our liturgy, trying to be as accurate in my translation as possible. The alternation between plain text and bold is for responsive reading. I invite feedback on the translation!

For the director.

By David.A fool said in his heart, “No God.”

They act destructively; they do abominable deeds;

There is no doer of good.Yahweh looks down from heaven upon the sons of Adam

To see if there is one who acts wisely,

Who seeks God.

The whole has turned aside;

Together they have become corrupt.

There is none who does good,

Not even one.Do they not understand, all the workers of wickedness,

Who eat up my people?

They eat bread;

On Yahweh they do not call.There they fear a fear,

For God is with the righteous generation.

The counsel of the oppressed you would put to shame,

But Yahweh is his refuge.Oh that from Zion would come the salvation of Israel!

When Yahweh returns the captivity of his people,

Let Jacob rejoice!

Let Israel be glad!

The first line of this psalm is often rendered, “There is no God,” which is probably a fine translation. But the quotation is not just a denial of God’s existence; it’s a denial of God’s relevance, a denial that God matters (“No God over me!”) or that God will act (“No God who will judge!”). God’s response, and that of David, is an echo of these words: “No one doing good.”

Later, “They eat bread; on Yahweh they do not call” may mean (as most translations have it) that they eat David’s people as they eat bread: David’s people are like bread that the wicked are gobbling down. But it’s also possible that it means (as James Jordan suggests) that they eat their daily bread but don’t call on the Breadgiver, the way Israel ate manna in the wilderness without thanking the Giver.

“Fear a fear” is a typical Hebrew expression, where the same root word appears as both the verb and the noun for emphasis.

The phrase at the end, “returns the captivity,” is used when God restores Job’s fortunes. It may refer to a return of captive people, but it may also refer to the restoration of anything that was lost. “Restores the fortunes” may be a good translation. Again, the verb and the noun have the same basic sound: “returns the returning” or “restores the restoration” might work, except that the second word is used, not for “restoration” but for that which has been lost and which one wants to have returned. I don’t know if there’s any good way to capture this in English.

Slow Reading

Recently, on a couple of my friends’ blogs, I’ve seen mention of this article about doubling the speed with which you read. [HT: Alastair and Pete.] There’s some stuff in that article which would probably be helpful for a lot of readers (e.g., finding your motivation and eliminating distractions).

Still, I wonder a bit about the value of speed reading. True, there are certain things that are worth only a quick read. There’s no point in slowly, painstakingly working your way through a lot of novels. And if you’re just reading for information, then it’s fine to skim or speed-read, looking for answers to your questions: “When was this town founded? What was its population then?” and so forth.

But not everything ought to be read at breakneck speed, and though (as this article points out) subvocalizing is the number one thing that slows down your reading, there are times when subvocalization is best, as the follow-up article says:

Subvocalization can be useful. Just like it isn’t always wise to read fast, sometimes it makes sense to subvocalize. My article focused on how to read faster, but sometimes you need to read slower. Better reading comes from having a brake and a gas pedal not just one or the other. If you are having trouble comprehending, slowing down so you start subvocalizing again can eliminate distractions and refocus your mind on the material.

I have to admit that I’m a notorious and unrepentant subvocalizer. I can read some things quickly and I don’t subvocalize all the time, but a lot of the time I’m saying the words in my mind as I read them.

I blame it on Walter Wangerin. Years ago, when I was just a teenager who wanted to be a writer, I read an interview with him, probably in Christianity Today. I can’t recall whether Wangerin said he subvocalizes when he read because he loves the sound of words and the way a good author puts them together or if he said it was the fact that he subvocalized as a kid that contributed to his love of words and good writing. One or the other: it doesn’t matter. I may have subvocalized before reading that article, but I did it deliberately after because I wanted to write and to write well and so I wanted to hear how good writing sounds to the ear.

I’m unrepentant, I say. I still love the sound of words and words together.

If I were to speed-read Dubliners I could get the gist of what James Joyce is saying, but I wouldn’t hear the stories and in particular I wouldn’t hear the voice of the narrator or the various characters speaking. Joyce used to write down conversations he overheard, I’m told, so that he could learn how to write dialogue the way it actually sounds. It must have worked: I was in Bible college with an Irish girl and I hear traces of her voice in everything Joyce writes.

I can’t imagine wanting to speed-read Joyce. Or Larry Woiwode, whose writing is always bordering on poetic and whose descriptions are so real it’s hard to believe that he hasn’t actually lived through exactly what he’s talking about himself. Or P. G. Wodehouse or Raymond Chandler or Ross MacDonald, all of whom use striking metaphors you don’t want to speed past.

Or Gene Wolfe, whose writing in many of his books is fairly easy to read and might fool you into thinking you can pick up the pace, but who is hiding clues in plain view. You could read through The Book of the Long Sun in a couple days if you wanted, especially if you’re reading 900 words a minute the way the writer of this article can. But you would miss the symbolism and all the puzzles Wolfe loves to include, and all you would get is a bare sense of the basic plot but little of what makes Wolfe worth reading.

And can you imagine skimming a poem? Yes, you could do it. You could catch the basic gist (“This one’s about how his love is like a red rose and this other one is about growing old”) but you’d miss the poem itself. Poetry depends on you listening to the words and even sounding them out.

It’s like food. You can wolf down a Big Mac and be out of the restaurant in a matter of minutes. But should you try to do that with your filet mignon and your glass of pinot noir in a classy restaurant? Or with the meal your wife made for dinner? No. Fast food has its place, but slow food is better. It’s better to take your time with a meal, to savor it, to visit with your family and friends and guests over the meal, to linger.

It’s okay to skim something quickly. It’s okay to speed-read some books. It’s sometime wise to skim a book first, get the gist of the argument and where the book’s heading, and then go back and read it more carefully. And sometimes you have only so much time and so all you can do is read as much as you can as quickly as you can.

But if you’re reading Scripture, read it slowly. In fact, the command in Scripture is not to read the Bible; it’s to hear it. And if you’re reading something beautiful, if you’re reading for the pleasure of words and the way they’re put together and to savor the writing or pick up the author’s clues or follow his arguments, slow down. Sound out the words in your head and enjoy them.

Speed reading? It has its place. But let’s hear it for the slow reading movement.

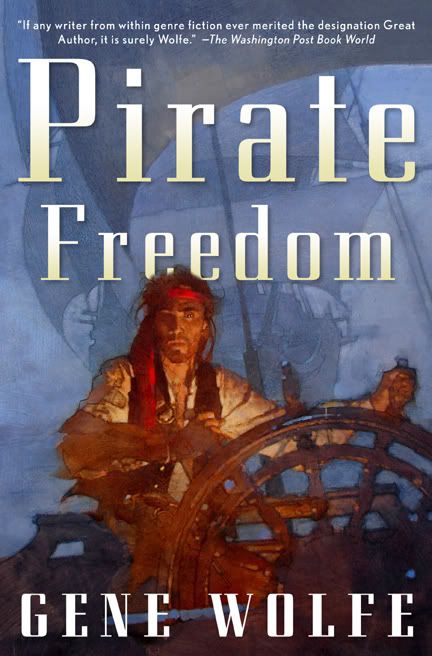

Pirate Freedom

Something to look forward to…. The latest novel from Gene Wolfe, coming out this fall. [HT: Irene Gallo.]

Â

Psalm 13

A reminder: I’ve prepared these psalms for our liturgy, trying to be as accurate in my translation as possible. The alternation between plain text and bold is for responsive reading. I invite feedback on the translation!

For the director.

A psalm.

By David.How long, Yahweh? Will you forget me continually?

How long will you hide your face from me?

How long shall I make plans in my soul,

With grief in my heart all day?

How long will my enemy be exalted over me?Look! Answer me, Yahweh, my God!

Enlighten my eyes lest I sleep in death,

Lest my enemy say, “I have overcome him.”

Lest my oppressors rejoice when I am shaken.But as for me, in your loyalty I trust;

My heart will rejoice in your salvation.

I will sing to Yahweh, because he has rewarded me.

Emerging Worship 3

A while back, I read Dan Kimball’s Emerging Worship and made a few comments about it. The book is due back at the library soon, so I guess I’d better finish up what I want to say about it while I still have the chance.

There were some things that pleased me about what Kimball says.  He points out that a lot of contemporary worship is man-centered, not Christ-centered (95). I appreciate that his congregation places the worship band in the back so that the musicians aren’t “on stage” as if they were performing for the congregation but are rather with the congregation, assisting them in singing (92).

I’m delighted to hear that the emerging churches often partake of the Lord’s Supper every week and that it’s becoming a central part of worship again (94).  I was glad to read that there’s “a revival of liturgy,” and an interest in the music of the past (92). Kimball says,

Interestingly, among emerging generations there is a fascinating revival of interest in singing hymns as part of worship. The lyrical content of many hymns is rich and deep, something emerging generations desire. The fact that we can become part of the church’s story by singing songs that are hundreds of years old demonstrates that Christianity is not a modern religion, but has deep historic roots. Some nineteenth and twentieth century lyrics are steeped in modernity, but many beautiful ancient hymns are worth including in emerging worship (pp. 93-94).

All of that was encouraging to me as a guy who’s trying to plant a liturgical church that sings lots of psalms and pre-19th century hymns. And yet….

At times it sounds as if Kimball and the emerging churches he’s describing are simply grabbing at whatever looks good to them. I notice that when Kimball talks about liturgy, he talks about it as an ancient practice. He speaks of the emerging generations’ “desire to seek the ancient” (92) and a sentence later uses the word “backlash,” which is what I’m afraid this is. It sounds as if the emerging church, in a backlash against sterile modernism (e.g., the church in a building that looks like a gym with a pastor in a business suit) is hungry for “cool old stuff.”

“Cool old stuff,” I say. It’s not just that they want everything ancient. It’s not that they want to adopt, for instance, the Book of Common Prayer and use that. It’s more that they think candles are cool or that Celtic crosses are cool or that prayer stations are cool or that “liturgy” is cool. It may be a backlash against modernism, but it doesn’t always appear to me from what Kimball says that it’s a backlash against the pursuit of the cool.

Another term for this “pursuit of the cool” might be the one Alexander Schmemann uses: mysteriological piety. In the mystery religions, people performed certain rituals because those rituals would create a sense of something “special,” something mysterious, something transcendent, or whatever.

The early church fell into this kind of piety when, for instance, it stopped doing baptisms immediately upon conversion or upon the birth of a covenant child and instead made Easter the day for baptisms. Why? Because baptism symbolizes death and resurrection and wouldn’t it make it more special to be baptized on the day we celebrate Jesus’ resurrection? Wouldn’t that make the symbol all that much more glorious, meaningful, and (if I may say it) “cool”?

Though Kimball says early in the book (I’ve lost the page) that he and his elders studied the Scriptures and jotted down all kinds of things from the Bible about worship, that study of Scripture is not evident in his discussion of worship. The Bible is rarely mentioned, in fact.

There are lots of quotations of Scripture in the margins, along with quotations from men such as A. W. Tozer, John Piper, and even John Calvin (“Lawful worship consists in obedience alone”: 149). But Kimball doesn’t present a biblical argument for any (that I can recall) of the practices he mentions, leaving the impression that what you do in worship is simply up to you. You might ransack history to find things you think are worthwhile if you have that “desire for the ancient” or you might dream up something new.

There are good reasons for some of the “ancient practices” Kimball mentions. There are good biblical reasons for weekly communion, for having candles on the communion table, and for following a liturgy (and not just any old liturgy), but there are also good biblical reasons for not following some ancient practices, reasons that our forefathers were right to point out. But Kimball doesn’t seem interested in reasons; he seems interested merely in reporting and celebrating diverse practices, and that’s disappointing.

What’s also disappointing to me is the individualism that pervades the emerging churches’ worship as Kimball describes it. He talks about churches allowing people to paint or write poetry or draw or sculpt clay during worship (85), which, I’m afraid, reminds me a bit of an elementary school art class, not worship. He mentions prayer stations: people move around the room and go to little enclosed areas where they can pray, and each one has something different in it, an object to handle or a project to do or a passage of Scripture somehow related to the theme of the service (86).

He stresses the importance of prayer in the service, but again it’s largely individual and spontaneous prayer: “Plenty of time is given for people to slow down, quiet their hearts, and then pray at various stations and with others” (94). Interestingly, he seems to associate the Spirit with contemplation and slow, meditative music (89, 94), though in the Bible the Spirit produces vigorous rhythmic music to say nothing of corporate music.

Later in the book, he describes a service at a church called Matthew’s House, where “They also take communion each week, and people can partake in communion at any time in the service when they are prepared to do so” (203). In other words: It’s up to you to partake if and when you want.

As he describes emerging churches in England, Kimball notes that there’s even less overt teaching and corporate singing than in North America. People are encouraged to “discover things for themselves” (214), which may fit with Kimball’s earlier statement that “Emerging preachers see themselves as fellow journeyers. Preaching is no longer an authoritative transferring of biblical information” (87).

Furthermore, these English emerging churches, Kimball says, have informal beginnings and endings. You come and go as you please. There’s some corporate stuff, but “it’s typical to say at the beginning that people don’t have to take part in anything if they don’t want to…. The event becomes a worship experience that one walks into and stays as long as one wants to” (214).

It strikes me that if Kimball truly wants a backlash against modernism, then this might be the place to start, with this sort of modern individualism with which our society is poisoned. Instead of fighting that poison and providing an antidote, however, these sorts of churches seem to be encouraging it. People are to come and feel free to do as they please; they aren’t to be compelled to join in a corporate song or a corporate prayer or a corporate anything.Â

Which is to say, they aren’t functioning in worship as a body.  They draw near to God and worship, not as the one body of Christ, acting corporately, doing things together whether they feel like it or not because it’s what the body is doing and it’s what Christ the head wants the body to do, but as individual marbles who happen to be in the same bag at the same time.

It may be that these churches work well as a body during the week. They may exhibit more “body life” than many other churches. I don’t deny that. But the individualism that pervades Kimball’s description of emerging worship is at odds with the church’s true nature as the body of Christ.

The good news may be that if there truly is a backlash against modernity, if people are open to “the ancient” and to liturgy and to Christ-centered preaching and to great old songs and to history, then there’s a great opportunity for the emerging church, perhaps after some adolescent struggles, to break free from the pursuit of the “cool,” to escape mysteriological piety, and most importantly to escape individualism and discover biblical corporate liturgy. If you put their zeal for authentic biblical community together with authentic biblical liturgy, you could have a potent combination.

Psalm 12

A reminder: I’ve prepared these psalms for our liturgy, trying to be as accurate in my translation as possible. The alternation between plain text and bold is for responsive reading. I invite feedback on the translation!

For the director.

On the Eight-String.

A Psalm.

By David.Save, Yahweh, for the loyal man has ceased to be,

For the faithful disappear from the sons of Adam!Emptiness they speak — a man with his neighbor;

Flattering lips: with a heart and a heart they speak.May Yahweh cut off all flattering lips,

The tongue that speaks great things,

That say, “With our tongue we will prevail;

Our lips are with us; who is our lord?”“Because of the devastation of the oppressed,

Because of the groans of the needy,

Now I will arise,” says Yahweh.

“I will place him in the deliverance he pants for.”Yahweh’s sayings are pure sayings,

Silver purified in an earthen furnace, refined sevenfold.You, Yahweh, will guard them;

You will preserve him from this generation forever.

All around the wicked walk,

When vileness is exalted among the sons of Adam.

In the fourth line, “with a heart and a heart” means that they have a double heart, perhaps one they show and one they hide, or one they show to some people and one they show to others.

The boast of the wicked, “Our lips are with us,” probably means “We own our lips; they’re ours.” It fits with the claim in the next line, namely, that they have no master (“lord”) to tell them what to do or say.

Irony or Immaturity

The setting: An Episcopal monastery. The characters: Brother Philip, an aged and frail monk, given to coughing, and Garret Keizer, 26 years old, who is wondering what to do with his life and whether to enter the ministry and has just asked Brother Philip for prayer about that matter.

The next day, after Sunday Communion, Brother Philip rushed past me toward the refectory with a purposeful energy that, in him, seemed nearly supernatural. For an instant I think I may have wondered if he had some prophetic thing to shout into the abbot’s face. He burst past several other monks and guests before stopping abruptly at the breakfast buffet, where he filled his plate with an almost obscene helping of bacon.

Over the years I have grown increasingly fond of this image, the memory of this monk, and bacon. At the time I saw nothing but irony — that young man’s sense of “Ah-ha, I see you!” For people such as I was, and have all I can do to resist being now, life is ablaze with epiphanies revealing the falseness all around us, when often nothing is revealed so much as our own immaturity. What we take for another eruption of the painful truth is just another pimple breaking out on our young soul’s face. Perhaps Brother Philip was teaching me an important lesson, the corollary to renunciation, that when you have chosen asceticism for your life’s work, and find yourself feeble and close to death, and the Lord deigns to provide you with some bacon, load up. — Garret Keizer, A Dresser of Sycamore Trees: The Finding of a Ministry, pp. 8-9.

Bruised Reeds, Smoldering Flax

During the Lenten season, Alastair has opened his blog to a number of guest bloggers whom he has invited to blog about matters relating to Jesus’ life and especially his suffering and death.Â

Today, my brief meditation, “Bruised Reeds, Smoldering Flax,” appeared. It deals with the passage in Matthew 12 where Jesus withdraws from the Pharisees who are plotting his death, heals the multitudes, and then tells them not to make him known in order to fulfill Isaiah 42’s prophecy about the Servant who will not quarrel, break bruised reeds, or snuff out smoldering flax. To give credit where it’s due, I’ll mention here that I’m following the exposition of this passage in Jakob van Bruggen’s commentary on Matthew.

The Moving Target

Today, I finished reading Ross MacDonald’s The Moving Target, the first of his novels starring the private detective Lew Archer. The Archer novels are noir, and this novel clearly owes a debt to Raymond Chandler, not only in the basic set-up (e.g., the tough but intelligent and sensitive detective who gets knocked around a fair bit) but also in his use of language.Â

Like Chandler, MacDonald crafts some interesting metaphors. For instance, describing a part of California where the extremely rich live, he writes: “The light-blue haze in the lower canyon was like a thin smoke from slowly burning money” (3). It works best if you can do a bit of a Humphrey Bogart voice-over in your mind as you read, though I suppose, considering that this book became the movie Harper, that the voice you choose to hear might be Paul Newman’s.

I liked these lines toward the end:

You can’t blame money for what it does to people. The evil is in people, and money is the peg they hang it on (p. 242).

If you like Chandler, you might want to try MacDonald. He’s no copycat, I gather, though I haven’t read enough of either to compare them, but they’re in the same camp.

Scotch

It was Jim Jordan who first introduced me to single-malt Scotch back in January 2003 at Steve Wilkins’ house. I can’t recall what we were drinking, though I suspect it was Glenfiddich. At any rate, apart from a couple times when I had Glenlivet, virtually all the Scotch I’ve had since then has been Glenfiddich.  I don’t drink it often, but it is something I enjoy sipping once in a while.

On Saturday evening, however, I tried something new. Moriah and I were out with her family for a meal at Porter’s, a great restaurant located in the old 1910 Medford train station. It happens also to be the restaurant where I proposed to Moriah. Someone else was picking up the tab, so I thought I’d try something different.

That something was a 10-year-old Laphroaig (pronounced La-FROYG). And it was indeed something different. The smell of it was a bit off-putting at first, a combination of permanent marker and leather. It tasted smokier than Glenfiddich, and it took a bit of getting used to. Even so, it didn’t become my favorite.

Since then, I’ve read online somewhere that many people prefer to add a dash of water which (I’m told) brings out the flavors better. Maybe I’ll try that sometime. The website makes me want to try it again, but then I’m a sucker for a website with stories about the men of previous generations who made the whiskey and who passed it on to the old guys who are making it today. It’s probably not made by a bunch of old guys. I’m sure the website wasn’t. But still, they know that when it comes to Scotch the sense of history hooks some people, people like me.

So having said all of that, I have to reiterate that I’m no expert when it comes to Scotch. So if you are, let me know. If Laphroaig worth trying again? And what else should I try the next time I’m out and someone’s offering to buy?