Category Archive: Literature

Western Union

Most fiction for kids and young adults is reviewed as if it existed in order to deliver a useful little sermon — “Growing up is tough but you can make it.” “Popularity is not all it’s cracked up to be.” “Drugs are dangerous.” …

The notion that a story ‘has a message’ assumes that it can be reduced to a few abstract words, neatly summarized in a school or college examination paper or a brisk critical review. If that were true, why would writers go to the trouble of making up characters and relationships and plots and scenery and all that? Why not just deliver the message? Is the story a box to hide an idea in, a fancy dress to make a naked idea look pretty, a candy coating to make a bitter idea easier to swallow? Open your mouth, dear, it’s good for you. Is fiction decorate wordage concealing a rational thought, a message, which is its ultimate reality and reason for being?

A lot of teachers teach fiction, a lot of reviewers (particularly of children’s books) review it, and so a lot of people read it, in that belief. The trouble is, it’s wrong….

I wish children in school, instead of being taught to look for a message in a story, were taught to think as they open the book, “Here’s a door opening on a new world: what will I find there?” — Ursula K. LeGuin, “A Message About Messages,” Cheek by Jowl, pp. 126-127, 129.

Lewis’s Sources

C. S. Lewis points out that the creativity in medieval literature is not generally found in dreaming up something new but in reworkingolder sources and doing new things with them. In C. S. Lewis and the Middle Ages

, Robert Boenig suggests that Lewis himself follows the medieval pattern: most of his fiction reacts to or builds upon earlier sources. Some are obvious; others are not. But it would be interesting, and doubtless profitable, to pair up a reading of Lewis’s novels with a reading of their primary source document(s).

Which sources does Boenig have in mind?

The Pilgrim’s Regress is, among many other things, his take on John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. Perelandra is his retelling of Milton’s Paradise Lost, composed after he heard Charles Williams’ 1940 Oxford lectures on Milton and penned his own critical work, A Preface to Paradise Lost. Till We Have Faces retells the myth of Cupid and Psyche from Apuleius’s The Golden Ass.

One can argue that the Arthurian romance The Quest of the Holy Grail, with some side glances at Sir John Mandeville’s Travels, is the major source for The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. The Silver Chair is, among other things, an homage to George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin and The Princess and Curdie. That Hideous Strength is his homage to the fiction of Charles Williams (79-80, paragraph break mine).

Boenig’s discussion goes on to focus on five books and their sources:

Out of the Silent Planet critiques H. G. Wells’s The First Men in the Moon.

Prince Caspian engages with William Morris’s Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair (which, in turn, had appropriated the thirteenth-century anonymous Middle English romance Havelok the Dane), wresting the story away from the sensuality Lewis perceived in Morris as both an attraction and a danger.

The Great Divorce redirects the medieval dream vision best exemplified in The Romance of the Rose, which Lewis had explicated so forcefully in The Allegory of Love, away from human love toward the love of God.

That Hideous Strength juggles criticism of T. H. White [The Sword in the Stone, but also the rest of The Once and Future King] with celebration of Charles Williams.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe becomes a vehicle for Lewis to suggest an important theological statement; the prior text to which he is reacting is the famous 1931 book Christus Victor by the Swedish theologian Gustav Aulén (80, paragraph breaks mine).

The Deadly Sin of Fiction Writing

In his entertaining book on writing fiction — not great literature, but fiction that will hook the reader and give him enjoyment — H. Bedford-Jones, “The King of the Pulps,” reveals what he considers to be the “deadly sin” that fiction writers often commit.

It’s not the lack of plot. Bedford-Jones himself was sometimes accused by editors of writing stories that didn’t have plots, novels that consisted of one episode after another, without one overarching plot that linked everything together. He argues that that sort of plot really isn’t crucial for a story, that there are great stories that lack that sort of overarching plot, though every paragraph of the story should be critical and no paragraph should be extraneous.

But what is the deadly sin? It’s the “lack of perception as to what must be emphasized, played up strong!” (46). It is the “lack of proportion in telling the story” (50). It’s … well, it’s what you’ve experienced from time to time when you’ve read a story:

You read a story, get interested in the characters, find the plot absorbing and good, entertaining. When you come to the climax, do you want to be told that the hero “knocked the skipper into the scuppers, overawed the crew, and took command of the ship?” Not much. You want the details of the knocking and overawing. You want to be on the inside, learn how the thing was done! In other words, you want to follow the emotions of the hero in detail.

Never forget that the reader, in general, identifies himself with the chief character of a story. He desires to see things through the eyes of that character. When the reader arrives at some crucial point in the tale and finds it glossed over in a couple of sentences, he is bitterly disappointed….

The amateur writer seems bound to commit this sin. He seldom realizes what points in his story he should lay most emphasis upon, and what points are least vital to his tale. It is a question of seeing the story in his own mind, of visualizing it, in its proper proportions. This perception of values, however, is something that he must come to learn unless he is to fail utterly. It is, undoubtedly, the great essential of fiction writing (This Fiction Business, 46-47, 48).

Pitter on Narnia

One of Lewis’s female friends (and yes, he did have some!) was the poet Ruth Pitter. Largely unknown today, Pitter was the first woman to win the Queen’s Medal for Poetry. She and Lewis met on occasion and exchanged a number of letters. I expect that she found it rather tiresome, after Lewis’s death, to have quoted to her and to be asked about what Lewis allegedly said to his friend Hugo Dyson: “I am not a man for marriage; but if I were, I would ask R.P.”

She writes about one meeting with Lewis and his brother, Major “Warnie” Lewis. Pitter had asked if she “might query him about the first of his children’s books,” and Lewis consented. She reports that the conversation went like this (Ruth Pitter, “Poet to Poet,” in In Search of C. S. Lewis, ed. Stephen Schofield, 113):

PITTER: In the land of Narnia, the witch makes it always winter and never Christmas?

LEWIS: Yes.

PITTER: Does she allow any foreign trade?

LEWIS: She does not.

PITTER: Am I allowed to postulate on the lines of Santa Claus with the tea tray?

LEWIS: You are not.

PITTER: Then where did all the materials for the good dinner the beavers gave came from?

LEWIS: The beavers caught fish through holes in the ice.

PITTER: Yes, the potatoes to go with them, the flour and sugar and oranges and milk for the children?

LEWIS: I must refer you to a further study of the text.

MAJOR LEWIS: Nonsense, Jack! You’re stumped. And you know it.

“Hope” in Pandora’s Jar (2)

A couple of weeks ago, I summarized Jean-Pierre Vernant’s thoughts on the “hope” (elpis: anticipation, expectation) left in Pandora’s jar when all the evils flew out. While some have presented the safekeeping of elpis in the jar as if it means that, in spite of all the evils in the world, man still has hope, Vernant sees the elpis as something closely associated with the emergence of the evils, something ambiguous. As he explains in his essay “The Myth of Prometheus in Hesiod” (in Myth and Society in Ancient Greece):

If in the Golden Age, human life held nothing but good things, if all the evils were still far away, shut up inside the jar (Works, 115-16), there would be no grounds to hope for anything different from what one has. If life was delivered up entirely and irremediably to evil and misfortune (Works, 200-1), there would be no place even for Elpis. But since the evils are henceforth inextricably intermingled with the good things (Theog., 603-10; Works, 178, to be compared with Works, 102) and it is impossible for us to foresee exactly how tomorrow will turn out for us, we are always hoping for the best. If men possessed the infallible foreknowledge of Zeus, they would have no use for Elpis. And if their lives were confined to the present with no knowledge or concern at all regarding the future, they would equally know nothing of Elpis. However, caught between the lucid forethought of Prometheus and the thoughtless blindness of Epimetheus, oscillating between the two without ever being able to separate them, they know in advance that suffering, sickness, and death is bound to be their lot, and, being ignorant of the form their misfortune will take, they only recognize it too late when it has already struck them.

Whoever is immortal, as the gods are, has no need of Elpis. Nor is there any Elpis for those who, like the beasts, are ignorant of their mortality. If man who is mortal like the beasts could foresee the whole future as the gods can, if he was altogether like Prometheus, he would no longer have the strength to go on living, for he could not bear to contemplate his own death directly. But, knowing himself to be mortal, though ignorant of when and how he will die, hope, which is a kind of foresight, although a blind one (Aeschylus, Prometheus, 250; cf. also Plato, Gorgias, 523d ae), and blessed illusion, both a good and a bad thing at one and the same time–hope alone makes it possible for him to live out this ambiguous, two-sided life. Henceforward, there is a reverse aspect to everything: Contact can only be made with the gods through sacrifice, which at the same time consecrates the impassable barrier between mortals and immortals; there can be no happiness without unhappiness, no birth without death, no abundance without toil, no Prometheus without Epimetheus–in a word, no Man without Pandora (200-201).

That’s Vernant’s view. Elpis is not a purely good thing; it is ambiguous, both the anticipation of good and the certain knowledge that–somehow, sometime–evil will come.

But what surprises me is that Vernant, at least in what I’ve read, doesn’t seem to see the elpis in Pandora’s jar in connection with the other parallels he so carefully works out in Hesiod’s accounts of Prometheus’s rivalry with Zeus:

* Prometheus tricks Zeus into accepting the worse part of the sacrifices and letting man have the best. He does so by taking the bones of the sacrifice and covering them up with lovely white fat. When Zeus sees them, he thinks they’re going to be especially delicious and so he chooses them as his portion, leaving man with the good meat, the better part, as his portion of the sacrifices.

* Zeus responds by refusing to let man have fire and by hiding man’s life (bios, here a reference to grain) in the ground so that now man has to work hard to get it. Bones hidden in fat correspond to bios hidden in the ground.

* Prometheus steals fire from Zeus and gives it to man.

* Zeus responds by making a “beautiful evil” (kalon kakon) for man that corresponds in some way to fire, namely, woman. In the Theogony, the woman isn’t named but is described as being the equivalent of drones who eat the honey the worker bees produce. A woman has a beautiful face and figure, but it hides a hungry stomach that gobbles up all a man’s earnings. In Works, Hesiod describes the woman, now called Pandora, as a beautiful woman who has a jar which, when opened, disperses evils among men. Once again, however, there is a correspondence: bones hidden in fat to look attractive to Zeus correspond, not only to grain hidden in the ground, but also now to an evil heart and a hungry stomach hidden inside a beautiful face and figure.

But right here I expected Vernant to say something about elpis. He notes that in the Theogony, “men are presented with a choice: either not to marry, and to enjoy a sufficiency of grain (since the female gaster [belly] does not take it from them) but not to have any children (since a female gaster is necessary to give birth) — the evil thus counterbalancing the good; or to marry and, even with a good wife, the evil again counterbalances the good” (Myth and Society 187). Elsewhere, Vernant puts it this way:

This is the dilemma now: If a man marries, his life will pretty certainly be hell, unless he happens on a very good wife, which is extremely rare. Conjugal life is thus an inferno–misery after misery. On the other hand, if a man does not marry, his life could be a happy one: He would have his fill of everything, he would never lack for anything–but at this death, who will get his accumulated wealth? It will be scattered, into the hands of relatives for whom he has no particular affection. If he marries it is a catastrophe, and if he doesn’t, it’s another kind of catastrophe.

Woman is two different things at once: She is the paunch, the belly devouring everything her husband has laboriously gathered at the cost of his effort, his toil, his fatigue; but that belly is also the only one that can produce the thing that extends a man’s life–a child (The Universe, the Gods, and Men 61-62).

Now we can put it together: It is only in Works that Hesiod tells us about Pandora’s jar; in Theogony, the “beautiful evil” is the woman herself. In fact, we could put it this way: woman herself is Pandora’s jar, a nice-looking vessel full of all kinds of evils. She is Zeus’s victory in his rivalry with Prometheus. She is the source of all evils in a man’s life, and in Works, she is the gift Prometheus warned Epimetheus not to accept from Zeus.

And yet, though the evils rush out from her, still elpis (hope, expectation, anticipation of the future) resides inside her. From the woman evils come into man’s life, but in the woman is the only hope the man has for the future, the hope of an heir–assuming that her all-devouring belly is also a fruitful belly and that the fruit it bears is a male child who lives and grows up to inherit a man’s property. And so the ambiguity of elpis that Vernant points out is maintained: a man gets married in the hope of an heir, and yet that hope is blind and uncertain (will she be fruitful? will she have a male heir?), so that elpis is both good and bad.

“Hope” in Pandora’s Jar

In the Greek myth of Pandora, she opens the jar and all the evils that were in it rush out into the world. By the time she gets the stopper back in, only one thing is left inside: elpis, which is often translated “hope.” And so, as the story is sometimes told, even though there are all kinds of evils and hardships in the world, we still always have hope. It’s kind of a positive ending to a sad story.

Or is it?

After all, what was this jar full of? Evils. Not evils and one good thing (hope). It was full of evils, full down to that last drop, elpis.

But how could hope be an evil?

In his essay “At Man’s Table,” Jean-Pierre Vernant takes a stab at an explanation. In Hesiod’s view, man has undergone a change from the way things used to be. Where men used to eat in fellowship with the gods, now there is sacrifice which not only provides some communion with the gods but also emphasizes the distance between them. Where food used to be free for the taking and the least effort could get you a year’s supply, now Zeus has hidden bios (life = grain) in the ground and you have to sweat to get it. Where there once were only men, now there are women (“beautiful evils,” as Hesiod describes them), who are like drones and dogs, gobbling up all that men produce and bring home. And where once everything was the same, day after day, now there is change.

And with change comes elpis: not hope (which for us is always positive) but, more broadly, expectation or anticipation. A man labors to plant his field and he cherishes the expectation (hope) of a good harvest. He labors during harvest in the expectation (hope) that he will have enough grain saved up that he and his family will be able to eat all winter and have enough to plant in the spring. His life is full of that sort of elpis, but he has that elpis only because he also knows that misfortune is coming. It’s not just that trouble might come: bad weather might destroy his crops; a fire might destroy his barn and all the grain he saved. Rather, it’s that he knows trouble is coming. Pandora let those evils out into the world and they’re roaming around, alighting on one person after another. You never know what’s coming. You never know when it’s going to be your turn. But you know one thing for certain: While things might go well for you for a while, trouble is coming. That’s elpis, and unlike those other evils that roam the world, striking here and there, elpis stays in the jar at home, because it’s something you have every day, all day long. It’s your constant but blind expectation: While you’re always hoping for good, evil will come and you never know when or how.

“Beautiful Evils”?

What did the ancient Greeks think about women?

Jean-Pierre Vernant, in a brilliant essay on Hesiod’s Theogony, explains. According to Hesiod, Zeus created the first woman to be a “beautiful evil” (kalon kakon) to afflict men. She would be a trap from which men could not escape. Though she appears beautiful on the outside, on the inside she has “the spirit of a bitch and the temperament of a thief” (kuneon te noon kai epiklopon ethos). You might be able to find a good wife, Hesiod admits, but even so, in and through her, “evil will come to balance out the good” (kakon esthloi antipherizei).

Women, according to Hesiod, are like drones: the men do all the work, and women sit at home and feed on the honey. Women are like flaming fire, burning and consuming but never satisfied. Women are stomachs, disguised by outward beauty, gulping down the food the man works so hard to provide. Women are like dogs, gobbling up the scraps.

That’s not just Hesiod. Vernant compares two passages in Homer’s Odyssey: “Is there anything more like a dog than the odious belly?” asks Odysseus, when he’s hungry. Elsewhere, Agamemnon says the same thing, but changes one word: “Is there anything more like a dog than a woman?”

Nevertheless, for the ancient Greeks, men are now stuck having to get married to women. On the one hand, they consume everything you’ve earned. On the other, you need them in order to have a (male) heir. They’re a trap, but one you can’t do without.

It is no wonder, then, that this first woman — whose name Hesiod gives in his Works and Days as Pandora — is the one who opens the jar that contains all the evils in the world and releases them on mankind (on males, that is).

What a difference there is when you turn from the ancient Greeks to the Bible, where the woman, far from being a “beautiful evil” is called “glory,” where the blame for the sin that brought death and misery into the world is attributed to Adam, even though Eve ate the forbidden fruit first, and where men are called, as co-heirs with them of glory, to show honor to their wives.

Intimations and Coincidences

In a recent blog entry, Doug Wilson pondered the potential significance of some coincidences that cropped up recently in his reading. I’ve had the same experience more than once, though, like Doug, I don’t know what weight or significance to attach to these experiences. They’re certainly not all profound or obviously meaningful.

The other day, just for the fun of it, I was reading a book about the old pulp magazines, which generated a blog entry on westerns and another on the amount of writing some pulp writers did and how much they were paid for it.

The other day, just for the fun of it, I was reading a book about the old pulp magazines, which generated a blog entry on westerns and another on the amount of writing some pulp writers did and how much they were paid for it.

In a chapter on the pulp hero named Operator # 5, there was a discussion of the novels in this series about the invasion of the United States by the Purple Empire, headed up (of course) by the Purple Emperor. There’s a picture of the first of those pulp novels to the right.

I set that book down and picked up Kenneth Grahame’s Pagan Papers (a dud, by the way; stick to his The Wind in the Willows and The Reluctant Dragon) and what should I find at the end of an essay on getting a bookbinder to put expensive bindings on your books? These words: “For these purple emperors are not to be read in bed, nor during meals, nor on the grass with a pipe on Sundays; and these brief periods are all the whirling times allow you for solid serious reading. Still, after all, you have them; you can at least pulverise your friends with the sight; and what have they to show against them?”

Two occurrences of the phrase “purple emperor” in the space of a few minutes. I’d understand that if either of these books was about butterflies (and I suppose Grahame may be making a metaphorical allusion to the purple emperor butterflies, though the allusion is not entirely clear to me). But what are the chances of finding that precise and unusual combination of words twice in two very different books, neither of them about butterflies, in the space of fifteen minutes? A big coincidence, certainly, but intimating … what, exactly? Probably nothing. Certainly nothing clearly. But then, why the noticeable coincidence?

Faster Than a Speeding … Pulp Writer?

In my last post, I mentioned The Waltons, a show that comes easily enough to my mind because I’m working my way through Season 4 right now with my family. Speaking of Season 4, in the fourth episode (“The Prophecy”), John-Boy is confronted by a professor who tells him that he’ll be very lucky if he can make a living as a writer. He says something like “There are only half a dozen writers in the United States right now who are able to do it.”

Perhaps he was referring only to what might be termed “serious literature,” which seems to be what John-Boy wants to write. (The creator of The Waltons, somewhat disappointingly, seems to have turned out only about three novels himself.) But if John-Boy had wanted to write for the pulps, he might just have been able to make a living. If he had been fast enough.

“Come now,” you say. “Surely the pulps didn’t pay that well.” Granted. They might pay a penny a word (as with the Texas Rangers series I mentioned in my previous blog entry) or perhaps $500 for a novel. Lester Dent, working under the house name Kenneth Robeson, started writing the Doc Savage novels at $500 a month and later received $750. The magazines themselves didn’t cost very much — maybe a dime — but some of them had a lot of readers. Within a couple of years from its first issue, The Shadow “was selling more than 300,000 copies” (Hutchison, The Great Pulp Heroes, 20). At a dime an issue, that’s $30,000 per month. Not bad, considering it was the Great Depression.

What kind of wages might a writer earn? That would depend on how many stories he sold, and that might depend on how fast he wrote. According to this site, wages in the early ’30s ranged from $0.35 an hour to $1.50 an hour (e.g., for a doctor). At an average of 21.67 working days a month and assuming only eight working hours a day, that’s $60.68 to $260 a month. Lester Dent’s $500 a month looks pretty good in comparison, doesn’t it?

But then consider a guy like Walter Gibson, who wrote The Shadow novels under the name Maxwell Grant. At first, he was writing only one novel a quarter, but soon it was a novel a month — and then the magazine started to come out twice a month: “he was to produce twenty-four adventures per year, one 60,000-word novel every two weeks for as long as the popularity of The Shadow continued. That figure totaled more than 1,440,000 words per year” (20).

If you do the math, that’s 692 words an hour, every hour, eight hours a day and 21.67 days a month, every month. Not 692 first draft, sloppy, “I’ll write them fast and edit them later” words. That’s finished product, ready to go. And that’s not 692 words per hour, after taking some time to think about your plot. If Gibson took some time for plotting, the actual writing was a lot quicker.

If you do the math, that’s 692 words an hour, every hour, eight hours a day and 21.67 days a month, every month. Not 692 first draft, sloppy, “I’ll write them fast and edit them later” words. That’s finished product, ready to go. And that’s not 692 words per hour, after taking some time to think about your plot. If Gibson took some time for plotting, the actual writing was a lot quicker.

And, in fact, it was: “Keeping two dozen yarns ahead of publication, he sometimes turned out a fresh book in four to six days, often working all night to meet self-imposed deadlines. Behind a typewriter, he was as superhuman as his own creation. He worked on a battery of machines. When one began to “get tired,” he’d move on to another, and then to a third (20).”

And he kept it up for eighteen years, for a total of 283 Shadow novels … among other things. Hutchison notes that the published guide to Gibson’s writing “is, in itself, a staggering 328 pages long” (29), and included “149 other books of all types, thousands of newspaper and magazine pieces, comics, radio shows, puzzles, mgic tricks, and other material under various pen names” (29).I don’t know what his income was per story. If he was paid a penny a word, that comes to $1200 a month. Maybe, like Dent, he received $500 a novel, but that still comes to $1000 a month — and that at a time when many doctors were making less than $300 a month.

Serious literature, John-Boy? No, you couldn’t likely have made a living writing that in those years of the Great Depression on Walton’s Mountain. But if you’d been writing for the pulps your father liked to read and if you wrote fast enough and well enough, maybe you could have. Apparently some people did.

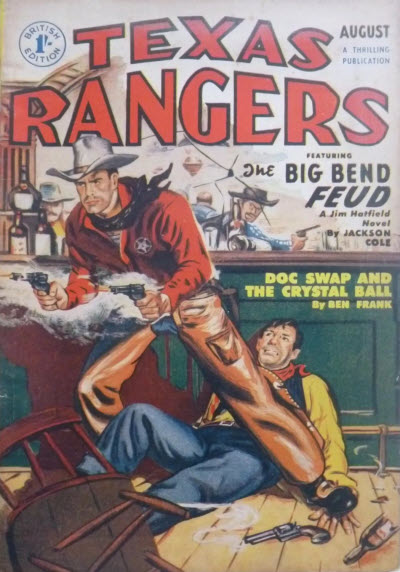

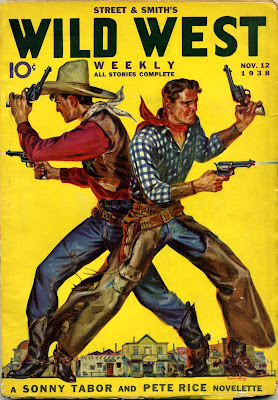

Westerns

It’s hard to imagine, but according to pulp magazine historian Don Hutchison, from the 1930s into the ’50s, there were at least “184 separate magazines devoted exclusively to Western fiction”:

In magazines with titles like Blazing Western, Wild West Weekly, and Western Round-Up, legions of dusty Galahads blasted six-gun trails to pulpwood glory. Vast and forbidding, the landscape of the American frontier produced one of the most alluring blank canvases in popular culture. Pulp Westerns, with their visions of high adventure and idyllic romance set in that perilous dream world, gloried in the nostalgic appeal of the uncivilized — total escape from anything that might be crowding you. They spoke beguilingly to the homebound reader of men and women with civilization at their backs who were never afraid and never bored” (The Great Pulp Heroes, 149).

Consider what sort of demand there must have been to make it worth a publisher’s while to put out just one of these magazines every week or even every month, year after year.

Then imagine how many voracious readers there must have been to gobble up 184 different magazines. (One of them was John Walton; true to real life, in many episodes of The Waltons, you see him reading a pulp Western magazine.)

Granted, some of those magazines probably folded after an issue or two. But others of them lasted for years. There were, for instance, Texas Rangers magazine published 206 novels about Texas Ranger Jim Hatfield in a series that lasted from 1936 to 1958 — and that, mind you, in spite of the dialogue, of which Hutchison says, “Some Western writers of the twenties and thirties considered it necessary to inflict painful cowboy slang and dialect on readers, as if their characters had studied under Gabby Hayes’ demented speech coach. Apparently, this was the way you were supposed to talk if you lived west of St. Louis” (151).

Granted, some of those magazines probably folded after an issue or two. But others of them lasted for years. There were, for instance, Texas Rangers magazine published 206 novels about Texas Ranger Jim Hatfield in a series that lasted from 1936 to 1958 — and that, mind you, in spite of the dialogue, of which Hutchison says, “Some Western writers of the twenties and thirties considered it necessary to inflict painful cowboy slang and dialect on readers, as if their characters had studied under Gabby Hayes’ demented speech coach. Apparently, this was the way you were supposed to talk if you lived west of St. Louis” (151).

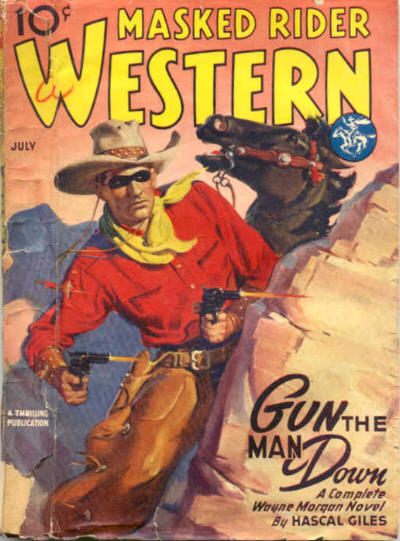

Mind you, the magazines that were most successful were not necessarily the ones you might have expected:

Despite his radio and comic strip fame, The Lone Ranger’s own magazine lasted but eight issues while his blatant pulp clone, the Masked Rider (who wore a mask and palled around with an Indian companion named Blue Hawk), galloped on for over one hundred numbers. Go figure (149).

Tragic Worship?

In a recent essay (“Tragic Worship“), Carl Trueman claims that the modern push for “entertaining” worship isn’t actually entertaining enough because it neglects tragedy, which is one of the highest forms of entertainment. He writes:

Perhaps some might recoil at characterizing tragedy as entertainment, but tragedy has been a vital part of the artistic endeavors of the West since Homer told of Achilles, smarting from the death of his beloved Patroclus, reluctantly returning to the battlefields of Troy. Human beings have always been drawn to tales of the tragic, as to those of the comic, when they have sought to be lifted out of the predictable routines of their daily lives—in other words, to be entertained.

From Aeschylus to Tennessee Williams, tragedians have thus enriched the theater. Shakespeare’s greatest plays are his tragedies. Who would rank Charles Dickens over Thomas Hardy and Joseph Conrad? Tragedy has absorbed the attention of remarkable thinkers from Aristotle to Hegel to Terry Eagleton.

What strikes me is that, with the sole exception of Shakespeare, everyone listed here as a great tragedian is a pagan or an unbeliever: Homer, Aeschylus, Williams, Hardy, and Conrad. In fact, the close link between paganism/unbelief and tragedy is so obvious that one of the proposed paper topics in one of my English classes in university years ago was on the possibility of Christian tragedy. One answer might be that when Christians, including Shakespeare, write tragedies, theirs are different: Shakespeare wasn’t writing Aristotelian tragedy, nor did he share the bleak despair of a Hardy, and even in the deaths of his characters, beauty shines out, the beauty in particular of virtue, the beauty of what’s good. While paganism is characterized by tragedy and despair, Christians embrace what Peter Leithart calls “deep comedy.”

But what puzzles me in this essay is what this tragic strand in Western literature has to do with the character of the church’s liturgy. Trueman writes: “Tragedy as a form of art and of entertainment highlighted death, and death is central to true Christian worship. The most basic liturgical elements of the faith, baptism and the Lord’s Supper, speak of death, of burial, of a covenant made in blood, of a body broken.”

But what Trueman seems to overlook is that the Lord’s death is precisely not tragic. The gospel of the cross doesn’t share in the “can’t fight the gods” fatalism of Aeschylus or its modern Hardyian form, nor is Jesus’ death like the deaths of Romeo, Hamlet, Othello, or Macbeth. We don’t feel good about Jesus’ death because in it we see man’s hubris being punished (Aristotle); we rejoice in it because in it man’s sin was dealt with and because, having death with sin, Jesus rose again. Remembering the Lord’s death in the Supper and remembering the death of Tess Derbyfield are two very different things.

Furthermore, while Trueman is correct in saying that “Death remains a stubborn … and inevitable reality” (I question his use of the word “omnipresent”), I don’t grant that “human life is still truly tragic.” Even in great western literature, not every death is tragic. When Aragorn kills an orc, there’s nothing tragic about the death of that orc. When Boromir rescues Merry and Pippin and then dies of his wounds, his death is sad but not tragic. When your grandmother falls asleep in Jesus, her death is sad, but not tragic — and beyond her death, there is the certainty of her bodily resurrection in glory, because in Christ death is swallowed up in victory. (And unlike Trueman, it seems to me that while the emphasis of the funeral ought to be on Christ’s triumph over death, there’s nothing wrong — let alone “most ghastly and incoherent” — with “the celebration of a life now ended.”)

Certainly, there is sorrow in this life. I agree with Trueman that Christians can and should lament. Paul tells us to sing psalms, and many of the psalms are full of lamentation. I’m all in favor of restoring the psalms to the Christian life and to the church’s liturgy, though I would add the caveat “as appropriate.” Why? Because it’s not appropriate for lamentations to predominate in the liturgy.

Trueman praises “the somber tempos of the psalter, the haunting calls of lament, and the mortal frailty of the unaccompanied human voice” of his Scottish Presbyterian tradition, but those adjectives — sombre, haunting, unaccompanied — hardly seem to fit with, say, Psalm 150 or with the descriptions of the Levitical choirs that David established or the heavenly choirs in Revelation. God apparently delights in accompanied singing (indeed, the word “psalm” itself implies accompaniment!), and apparently he likes it loud and vigorous, at least much of the time.

Trueman claims that “traditional Protestantism” connected “baptism not to washing so much as to death and resurrection.” That’s as may be — washing is certainly as valid a connection as death and resurrection — but again, the death associated with baptism, linked so closely with resurrection, was far from tragic. He points to the reading of the law every Sunday: “Only then, after the law had pronounced the death sentence, would the gospel be read, calling them from their graves to faith and to resurrection life in Christ.” Leave aside the question of whether the reading of the Ten Commandments before the confession of sin tends to emphasize the so-called “first use” of the law instead of its primary use as a rule of life and even grant the questionable assertion that the reading of the law “pronounces the death sentence” and apparently carries it out (so that believers are in “their graves” after it!), we still have a progress from death “to resurrection life in Christ” — so why should the rest of the service be sombre as if we were still dying or dead?

Is there room for sorrow in the Sunday service? Perhaps, in measured doses. It’s not inappropriate to sing Psalm 51 in connection with the confession of sins. On occasion, it may be right and fitting to sing a lamentation. But what ought to be the dominant note of our worship, even when we’ve been deeply convicted of our sins? It certainly isn’t tragedy. Nehemiah 8 points the way:

Then Nehemiah, who was the governor, and Ezra the priest and scribe, and the Levites who taught the people said to all the people, “This day is holy to the Lord your God; do not mourn or weep.” For all the people were weeping when they heard the words of the law. Then he said to them, “Go, eat of the fat, drink of the sweet, and send portions to him who has nothing prepared; for this day is holy to our Lord. Do not be grieved, for the joy of the Lord is your strength.” So the Levites calmed all the people, saying, “Be still, for the day is holy; do not be grieved.” All the people went away to eat, to drink, to send portions and to celebrate a great festival, because they understood the words which had been made known to them.

Books I Enjoyed Most in 2012

Last year, I must have been exceptionally industrious. I see that I managed to post my list of favorite reads from 2011 already in January 2012. This year, I’m a little behind. But here it is, at last, listed alphabetically by the author’s last name.

* Louis Berkhof & Cornelius Van Til, Foundations of Christian Education. Great essays; often outstanding insights.

* Po Bronson & Ashley Merryman, NurtureShock: New Thinking About Children. Fascinating and very helpful stuff on, e.g., the effect of praise on children, children’s intelligence tests lacking validity, how kids learn to speak, the importance of sleep for children.

* Walter R. Brooks, The Clockwork Twin. Read to kids. The fifth Freddy the Pig novel; some passages had me howling with laughter.

* John Buchan, The Three Hostages. One of my favorite authors.

* G. K. Chesterton, The Collected Works, vol. 27, The Illustrated London News, 1905-1907 and The Defendant. Wonderful essays.

* Elizabeth Coatsworth, Away Goes Sally, Five Bushel Farm, and The Fair American. The first three in a series of books about a young girl in Maine in the late 1790s. Read to Theia and Vance, with much enjoyment.

* Joy Davidman, Smoke on the Mountain: The Ten Commandments in Terms of Today. Insight after insight.

* Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows. A masterpiece.

* Stanley Hauerwas, Carole Bailey Stoneking, Keith G. Meador, and David Cloutier, eds., Growing Old in Christ. Very helpful essays, many of them rich with insights.

* C. J. Hribal, Matty’s Heart and The Clouds in Memphis. Stories that can break your heart.

* Rachel Jankovic, Loving the Little Years: Motherhood in the Trenches. Not just for mothers; I need to read this one every year.

* Walt Kelly, Pogo: Through the Wild Blue Yonder: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, Vol. 1. I grew up reading these in books my parents had collected. It’s great to see them coming out in a nice hardback edition. There has never been another comic strip like Pogo.

* C. S. Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew and The Last Battle. Great stuff … though I’m glad the eschatology Lewis presents for Narnia isn’t the eschatology of Earth.

* C. S. Lewis, Miracles. I remember trying to read this when I was much younger (a teenager?) and not getting very far. Loved it this time through.

* Richard Lischer, Open Secrets. An enjoyable memoir of the first year of a Lutheran pastorate in southern Illinois; some very good passages on pastoral work, including an interesting and helpful chapter on the often positive function of gossip — “speech among the baptized” — in a church community, as it sorts out people and relations and evaluates them.

* Eloise Jarvis McGraw, The Golden Goblet. Read to Theia and Vance at the same time I was teaching Theia about ancient Egypt.

* A. A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner. Read them to the kids … again. There were times I could hardly stop laughing. I ought to read these every year.

* E. Nesbit, The Story of the Treasure Seekers. Hilarious. Why didn’t I read Nesbit when I was a kid? Especially puzzling, given that I loved C. S. Lewis and Edward Eager.

* Patrick O’Brian, The Thirteen Gun Salute, The Nutmeg of Consolation. The thirteenth and fourteenth in a series that never gets stale.

* Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping. Slow but deep.

* P. Andrew Sandlin & John Barach, eds., Obedient Faith: A Festschrift for Norman Shepherd. I first met Norman Shepherd when I was in seminary and he was a member of the board, and it was an honor to be able to edit this volume for him. There are some very good essays in here.

* Lynn Stegner, Because a Fire Was in My Head. Very realistic and very sad.

* Victoria Sweet, God’s Hotel: A Doctor, a Hospital, and a Pilgrimage to the Heart of Medicine. Very interesting account of a doctor at the last almshouse in America and the change from “inefficient” to “efficient” medicine, with some interesting stuff on premodern medicine, medical politics, etc.

* Hilda van Stockum, A Day on Skates. Very enjoyable.

* J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit. Second time through with the kids. Maybe I’ll tackle The Lord of the Rings this year.

* Lars Walker, Erling’s Word. Blogged about it here.

* Laura Ingalls Wilder, These Happy Golden Years. Read to the kids with as much enjoyment myself as they received.

* N. D. Wilson, Leepike Ridge. Had the kids on the edge of their seats a lot of the time. Or their beds. Wherever they were sitting, it was the edge. Someday, they’ll read The Odyssey and remember this story.

* N. T. Wright, The Epistles of Paul to the Colossians and to Philemon: An Introduction and Commentary. I find Wright’s approach to the so-called “Colossian heresy” quite persuasive.

If there’s one thing to learn from this list, I guess, it’s that most of the best books I read last year were the ones I read with the kids.

.jpg)